5 important things to know about growing nutrient-rich grass for livestock

Growing good quantities of quality grass doesn’t take a science degree or a large investment, but it does require care and common sense.

Words & images: Sheryn Dean

Growing grass isn’t as complicated as I once thought. I have talked to fertiliser salespeople who push their products but often can’t justify why I need them. I’ve read books and attended pasture seminars. I’ve tried to understand the interactions and complexity of the elements.

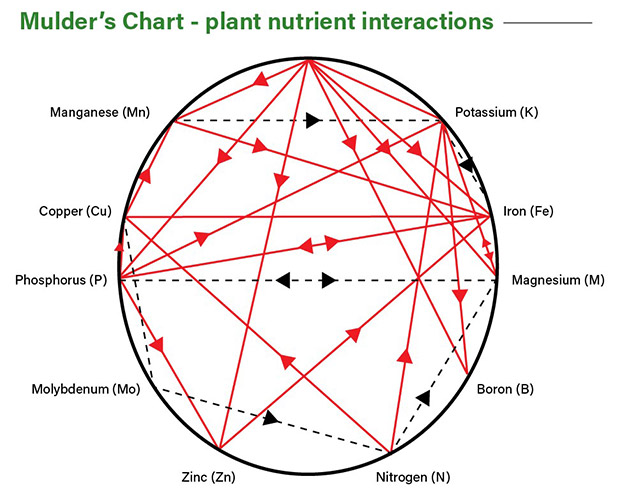

Have a look at the Mulder’s chart below and see if you can make sense of it. I’ve concluded that growing grass is rather simple. All you need to do is get outside, look at your grass, note how it grows, and how your animals eat it.

Lesson 1: Remember the nutrient cycle

If you continuously take fruit from a tree or graze livestock on pasture, you need to ensure an equal amount of nutrients are returned to the soil. You can’t continually take from the land without giving something back or lowering soil and pasture quality.

Livestock and soil microbes like a diverse range of pasture plants.

One of the easiest ways to add nutrients to pasture is to buy in quality feed for your stock. They digest it, partially ‘compost’ it, spread it around the paddock, and grow meat, at the same time. If you cut and sell hay or silage, you are selling nutrients off your land.

Lesson 2: Nitrogen, but not as you know it

Nitrogen is one of the critical components of grass growth. It’s also free and all around us; air is 78 percent nitrogen, so all you need to do is ‘harvest’ nitrogen from the very air we breathe. So why do farmers use urea (nitrogen fertiliser) instead, and why the big concerns about leaching?

Plants are unable to take up nitrogen. It needs to be converted into nitrates before they can use it. Humans worked out how to do this and created urea, which gives plant growth an instant boost. Unfortunately, urea isn’t stable in soil, so it leaches out when it rains, accumulating in waterways.

There is a natural process that turns nitrogen from the air into nitrates – microbial action. Microbes hold the nitrogen in a stable form until the plant requires it.

Rather than spending a lot of money and time applying fertiliser to your land, it makes a lot more sense to nurture these microbes and let them do the work for you.

Lesson 3: Lime

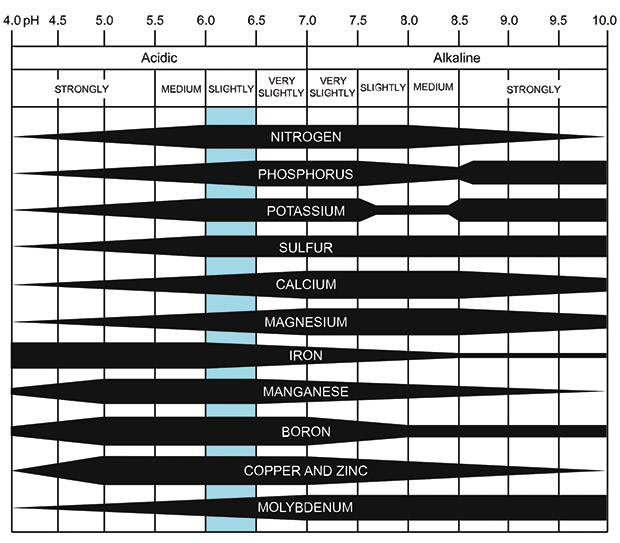

Mulder’s chart shows there are a LOT of chemical interactions, but soil pH is the easiest to understand. The acid-alkaline balance of your soil affects most other elements. Too acidic and these elements become ‘locked up’ and unavailable to

your plants. It’s rare for NZ soils to be too alkaline.

Lime ‘sweetens’ the soil (makes it more alkaline). You can send soil samples to a lab for an $80 basic test, or you can buy

a $30 testing kit from a garden centre to find out your pH. Tip: don’t buy a pH probe, I’ve found them useless.

The ideal pH for ryegrass and clover is around 6.0, or slightly acidic (neutral is 7.0). Soil with a pH under 5.8 will benefit from the addition of lime. You need to apply a decent amount, depending on your soil type and the quality of the lime. It can take a ton of lime per hectare to raise the pH 0.1 point (ie, from 5.8 to 5.9) so be liberal.

You can buy lime in one-ton bags from a fertiliser company. Bring it home on the trailer (or get them to deliver it) and throw it out by hand or hire a towable fertiliser spreader. Alternatively, you can pay a contractor to supply and spread it for you.

The effect of soil pH on nutrient availability.

I don’t hold with the theory that lime needs to be applied annually. If a test shows your soil pH is low, bringing it up into the ideal range creates the right environment for grass growth and soil life. Once it’s there, it should be stable, unless you are applying fertilisers which acidify the soil again.

Lesson 4: Trace elements

All the microbes in the world can’t magic something from nothing; if your soil is lacking an essential element, you need

to supply it. There are a lot of trace minerals, and testing for them is expensive. Not all of them are essential for grass growth but may be crucial to livestock (and you, if you eat the meat).

Trying to establish what is missing and how to apply it is complicated and often unnecessary. You can assume a few are lacking, such as the following, and apply a general supplement.

Selenium

Most New Zealand soils are low in selenium. Grass doesn’t need selenium, but your animals do. If you are eating your animals, it benefits you too.

Cobalt

This is known to be lacking in the volcanic ash soils of the central North Island and the granite soils of north-west Nelson. It may be lacking in other areas and soils – a good local vet will know. Animals convert cobalt into B12.

Boron

This is another micronutrient commonly lacking in New Zealand. Again, it’s not necessary for grass growth, but it is essential for other crops, especially fruit trees.

If you are buying lime from a fertiliser company, you can get any of the these mixed through it – the extra cost is minimal.

There are a lot of other minerals, vitamins, electrolytes, and trace elements which will probably benefit your soil. These elements get leached into the waterways and eventually out to sea where they are taken up by fish and seaweed.

Applying seaweed or fish fertiliser is an easy way to provide a balanced and comprehensive range of nutrients. It can be as simple as buying a ready-made extract to spray on pasture. You could forage seaweed off the beach (or buy it dehydrated) and make a seaweed tea (the same way you make compost tea). You can also offer dried seaweed (or seaweed meal) to your stock to eat.

Lesson 5: Take care of microbes

If you think your pasture is lacking soil microbes from previous bad management, you can seed good microbes by adding

a good quality compost or compost tea. Soil microbes, given the right conditions, will eventually repopulate themselves.

How to nurture microbes

If soil pH is around 6.0 and nutrients are available, microbes and the other organisms will convert manure and decaying organic matter into food that helps grass growth. All you need to do is nurture them.

Microbes are living organisms. They need air, moisture, warmth, food, and a safe environment to survive and flourish.

How to feed microbes

Microbes feed on the carbon and proteins of decaying matter, and the sugars they get from the plants. Adding compost and fallowing your pasture (leaving pasture plants to grow, un-grazed for up to a year) are two easy ways to provide organic matter, and quickly boost your microbial population.

Growing more, and larger, plants to provide more roots for them to feed on maintains a high population of microbes.

Microbes do best if they can access a diverse range of plants. Different species of grasses and trees provide different roots which exploit different spaces within the soil, offering a variety of food options for different microbes. Your stock will also appreciate a diverse range of grasses and shade trees.

Microbes form a symbiotic relationship with the roots. The more roots you have, the more microbes you have. The more leaf area you have, the more roots you have. Longer grass has more roots and supports more microbes than short grass.

Only graze the top half of pasture, which leaves a lot of leaf area to continue photosynthesis. You won’t be wasting this grass: it will re-grow more quickly than pasture grazed lower, thanks to the extra leaf area for photosynthesis and additional microbes on its abundant roots. Top ungrazed weeds with a mower (set high) to help them break down, and to ensure they don’t flourish and dominate your pasture.

GIVE MICROBES THE RIGHT ENVIRONMENT

We are trying to grow grass to feed our stock, but that’s not necessarily the original purpose of that patch of soil, which once may have supported native forest or wetland.

If we want the microbes that sustain and feed grass, we must provide the right environment for those microbes:

• not too wet;

• not too dry;

• warm (above 10°C);

• not compacted or waterlogged.

SHERYN’S TIPS FOR BUYING HAY

If you’re buying in hay, leaf quality is paramount. You also want to avoid bringing in weed seeds. Ideally you would inspect the pasture and measure the brix levels to establish its quality before cutting for hay, but this is rarely possible for a small purchaser.

A more likely option is to buy direct from one trusted, local source every year. This way, you can see how they manage their pasture for yourself. If you can establish an ongoing arrangement, offer to collect it on harvest in exchange for a lower price.

WHY VERY SIMPLE SOIL CAN DO MAGIC

Microbes are single-celled organisms that live in the soil. For millennia they have interacted with soil and roots to make everything grow. They digest soil nutrients into a form the plants can use. In return, the plant produces sugars (through photosynthesis) and swaps them for nutrients.

This mutually beneficial trade is called a symbiotic relationship. Microbes are only the start of a complex web of life in the soil. They eat organic matter; in turn, they’re eaten by nematodes, protozoa, and mites which are eaten by worms, beetles, ants, and spiders. Larger predators then eat them, and so on.

One teaspoon of live soil can contain millions of different bacteria and metres of fungi hyphae. We can’t see them with the naked eye, but we can smell them: a healthy soil full of the right bacteria and fungi has a pleasant, sweet, ‘earthy’ smell.

DO YOU NEED A SOIL TEST?

Those in the industry will tell you a soil test (or a herbage test) is essential. Farmers are constantly told they need annual applications of fertiliser for grass growth. I disagree.

When you first start working with your soil, testing gives you an idea of any major deficiencies and its pH. I think it’s more useful to regularly walk through your paddocks and look at the grass and soil:

• is the grass green and healthy-looking?

• is it growing?

• what weeds are around? If there’s a lot, it means the soil conditions are optimal for the weeds, not the grass you want to grow.

• dig up a ‘spit’ (one spade width wide by one spade width long by one spade width deep), and smell it. Count the number of worms. How does it feel?

Noting these down throughout the year is a good indication of how your soil is working. Make regular observations, and you’ll soon start to notice differences. The guide below is a helpful, practice guide, showing you what looks good and what doesn’t.

Sheryn’s tip: Download the Visual Soil Assessment Field Guide for excellent guidelines on how to evaluate your soil.

3 COMMON WAYS TO MURDER MICROBES

Whatever you do, don’t kill the soil’s microbial life. They won’t survive if a whole lot of artificially manufactured chemicals are dumped on their heads. If you contaminate their environment with sprays or fertilisers, they’ll strike, leave, starve, or die.

1. Spray with fungicides, herbicides or insecticides

This includes organic sprays – organically ‘dead’ or chemically ‘dead’ things are still dead. While you might be spraying for a specific disease or weed, anything that has ‘–cide’ in its name can kill fungi and bacteria.

2. Apply chemical fertilisers

By this, I mean urea or superphosphate. At low rates, these prevent microbes from growing; at higher rates, they kill them.

3. Compacting the soil

Badly pugged soil is low in oxygen, and pasture will be much slower to grow.

Driving over a pasture, or livestock ‘pugging’ it (squashing out air pockets in the top layers) will suffocate microbes.

MORE HERE

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.