Nelson Lebo’s top tips to help your block survive flood and natural disasters

Climate change is the greatest challenge facing rural New Zealand. Here’s how simple planning and design can make your block more resilient to natural disasters.

Words: Nelson Lebo

Who: Nelson & Dani Lebo

Where: Kaitiaki Farm, 10km east of Whanganui

What: permaculture, regenerative agriculture

Land: 5.1ha (13 acres)

I’ve seen fire and I’ve seen rain. Unlike James Taylor, I was relaxing, shirtless and shoeless on the couch after a long day working outdoors in March 2020, just before the first Covid lockdown. Sounds of dinner prep were coming from the kitchen. Then I heard my wife ring a neighbour and say, “Do you see smoke down in the valley?”

Minutes later, I was halfway down the hill, still shirtless and shoeless, beating out a grass fire with the back of a shovel and shouting instructions to our permaculture interns who were fast on my heels. A strong north-westerly wind was carrying flames up the valley through the dry autumn grass and gorse toward our home and three others. Our small team was able to slow its advance long enough for the fire service – who arrived at sunset – to take over the battle into the night. Hours later, they finally dowsed it, although we had multiple flare-ups over the following two days.

- The damage caused by a fire in dry grass in autumn 2020. digging in the poles along a steep hill with permaculture interns Patrick and Kelly in 2016.

- Poplar poles from our regional council.

- The poles are soaked in water for 7-10 days before planting.

The fire’s path was uphill and across a large slip that occurred during major flooding in the Whanganui Region in 2015, just 11 months after we purchased the property. The slip was one of three resulting from the storm, among the thousands on surrounding farms. While that fire scared us, it’s the slips that have set us on the course of building a more climate-resilient block.

Climate change isn’t a gradual and gentle warming of temperatures but increasing incidences of extreme weather events. Too much water. Too little water. Too much wind. We’ve experienced all of these on our block and have spent the last six years planning and designing for climate resilience.

Digging in the poles along a steep hill with permaculture interns Patrick and Kelly in 2016.

The historic 2015 storm dropped around 150mm of rain in one night, and it was the event that focused our work. We started by planting 30 x 3m-long poplar poles supplied by Horizons, our regional council. We planted the first ones in August 2015 and have added 15-30 more each winter since for a total of about 150 so far.

We initially planted them to help stabilize vulnerable hillsides but later discovered their value as a late summer fodder crop for our goats. The poplars provide excellent browse when the soil is at its driest, and most grasses are essentially dormant. We’ve also planted dozens of willow wands along one eroding section of stream.

The poplars are a way to address both ends of the climate spectrum – wet and dry – so I looked for other strategies that could do the same.

WHY PLANT POLES?

A poplar or willow pole is a young tree stem from 1-3.5m long which roots and sprouts when planted in the ground. Poles grow much faster than seedlings and are less likely to be damaged by browsing animals.

WONDERFUL WETLANDS

One year after the big 2015 storm, we were ready to take big steps, assisted again by Horizons Regional Council thanks to partial funding from its Sustainable Land Use Initiative. We put up nearly 1km of fencing along Purua Stream and planted 300 native trees, shrubs, grasses, and flaxes with the help of the local school, Te Kura Kaupapa Maori o Tupoho.

- Before (2016).

- After (2021).

- Our children playing by a small creek back in 2016.

- The same area, now planted in natives in 2021.

We’ve since planted thousands more along the riparian corridor and across two former wetlands. I’m a former high school science and ecology teacher, so I’m familiar with the benefits of wetlands, including:

• biological diversity;

• wildlife habitat, eg breeding grounds and nurseries;

• water filtration and purification;

• stormwater buffering and retention.

We’ve planted over 2000 plants along 500m of stream at the bottom of the property.

While we value all of these, their buffering effects have helped us to simultaneously flood-proof and drought-proof the farm. Wetlands are like a good savings account, holding water in times of excess and releasing it in times of scarcity. They’re also referred to as giant sponges for their absorption capacity and nature’s kidneys for their filtration ability.

4-DIMENSIONAL WATER MANAGEMENT

We’re continually adding to our wetland using nature as our design muse. For the most part, nature favours moderation over extremes. It usually finds ways to diffuse, delay, disperse, and distribute large water volumes that threaten to disrupt its equilibrium. We’ve also added ‘de-compact’ and ‘divert’ to our land management strategies.

A large, hand-dug pond at the top of the property holds water in winter and releases it in summer.

Our approach is a network of swales, drains, and a small pond, which allows us to delay, divert, disperse, and distribute stormwater. We can diffuse the forces of water rushing downhill and store winter rains for late spring and early summer use. We employ a similar approach with gutters, downpipes, water tanks, and runs of corrugated plastic drainpipes to:

• delay stormwater surges and divert water away from vulnerable slopes at certain times of year;

• delay/divert water to dry areas at other times of year.

For each roof on the property – and we have a fair few – rainwater follows a path directed by the time of year with distinct winter and summer modes. We use a combination of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ engineering options, and both are sensitive to seasonal changes. Many of the hard options are designed to be replaced by soft options over time. One example is the wind netting we’ve used to establish our orchards.

Almost any resource on a property can be an asset or liability depending on quantity and timing (eg, 100mm of rain in one weekend, or over a month). What we do – using nature as our guide – is try to minimise or eliminate liabilities while maximizing assets.

Soil moisture is a good example. Many blocks are pugged for much of the winter, then bone-dry over summer. This is usually due to:

• soil compaction;

• low soil pH;

• poor soil biological activity.

We’ve addressed those issues on much of the land by choosing lighter animals over heavier animals, adding lime and wood ash to soil, and ‘top-feeding’ soil life with manure from chooks, ducks, and goats.

WHAT IS A SWALE?

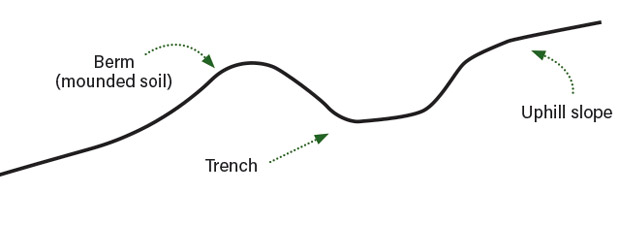

A swale is a berm (ditch + mound) that is perpendicular to a slope. It looks like a drain but is perfectly level, so water only exits when it soaks through into the soil or evaporates. Although built by hand or machinery, swales mimic natural wetlands; they slow and store stormwater, which helps mitigate the peaks of floods and droughts.

WIND FENCING WITH NATURE

We first erected a wind fence for our main orchard shortly after we arrived to protect the young fruit trees from the prevailing northwest winds. The following winter, I planted two staggered rows of harakeke (flax) on the windward side, dividing plants already on the farm. Once the flax grew to 2m – as tall as the wind fence – we took it down and moved it, posts and all, to protect a new avocado orchard in a different area.

- Before (2016). Replacing a wind fence made from plastic netting, steel wires and treated timber with one made from roots, leaves and flowers.

- During.

- After (2021).

We replaced a ‘hard’ wind barrier that breaks down in sunlight and water with one that thrives and grows with sunlight and water. I believe this kind of ‘soft’ engineering is almost always more robust in the long run. Even some of our corrugated plastic pipes are intended to be temporary stormwater solutions as we establish deep-rooted trees on slopes most vulnerable to slips.

SOFT VS HARD ENGINEERING

Hard engineering: artificial structures built by humans to control or direct forces of nature.

Soft engineering: more natural and sustainable options. On our block we refer to them as ‘physical’ and ‘biological’ approaches to wind and water management.

WHY THINGS NOW BEND, BUT DON’T BREAK

I’m not an engineer, but my observation is that when hard engineering fails, it fails spectacularly. Soft engineering seems to be a lot more flexible. Case in point, just before I submitted this article, Whanganui received 62mm of rain in one night, causing surface flooding and some evacuations. This morning when I went to check everything, I found a lot of water about the place but no slips on the hillsides and no major erosion of the stream banks. Six years of working with nature appears to have paid off.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.