Explore the regenerative track in the Coromandel with a royal seal of approval

Linden on what is known as Sue’s Bridge (in honour of a friend) which traverses the erosion created by a windfallen pine.

What started as a retirement dream grew into a passion project to nurture and protect a native forest for future generations.

Words and images: Sheryn Dean

Who: Linden and Richard Moyle

Where: Tihana, Te Mata, Coromandel

What: Five hectares protected native bush

When searching for a retirement block in 2000, Linden Moyle viewed a steep sheep farm covered in rank grass and gorse in Coromandel’s Te Mata valley. It was not love at first sight. Rain obscured the view and the wind whipped around her. But it did have her husband Richard’s prerequisite – a north-facing house site on a hill. A return visit on a clear day revealed a vista up to Coromandel Forest Park and a window down to the Firth of Thames. It was then that Linden knew it was where she wanted to be.

Five of the ten hectares had been fenced and grazed. The rest was a jungle of wilding pines, weeds, and bush perched over steep faces. The land was so steep they couldn’t venture below the paddock fence. “We couldn’t see the property,” says Linden. “There was no vantage point. We bought the property for the house site and the bush came with it.

Celery pine or tanekaha are prolific amongst the bush.

“It was two to three weeks after the purchase before we found the river – and wow! Then we discovered the wetland. It just kept getting better and better and better.”

Neither had prior knowledge or experience of farming or gardening. They tried running a few sheep, letting the neighbour graze their cattle and offering the land to Unitec horticultural students for project use. “But Unitec wanted us to oversee the project, do soil tests, monitor and report. So I decided to enrol and do the course myself,” Linden says.

Linden, who had previously only stuck a few tomatoes in her urban section and wondered why they hadn’t produced, reckons her horticultural genes kicked in. Her grandfather had been a pastor and notable native conservationist in Wellington in the 1960s. Through the course, she obtained a broad overview on everything to do with growing plants and became interested in native plant regeneration.

The Coromandel Forest Park on the horizon behind Linden and Richard.

“It is the logical thing when looking after this sort of land. You let nature do it for you.”

She started off in 2000 planting lemonwood and pōhutukawa, neither of which grew naturally in the valley. She learnt to observe what belonged, eventually seed-saving from the existing forest and growing over 10,000 plants. She focused mainly on local pioneering species: kānuka, putaputaweta, māhoe, karamu and akeake.

Her work has recreated the bush that once clad the hills, extending the adjoining Coromandel Forest Park into a native corridor down the valley.

Protecting a legacy

Nīkau and punga regenerate in the wetland.

While the couple are extremely proud of their work, simply regrowing the forest was not enough – they felt they needed to safeguard it for future generations. This was influenced by the experience of Linden’s grandfather, whose own conservation efforts were squandered. He had filled five hectares in Wellington with rare native plant specimens he gathered from throughout the country. However, the 1968 storm which sunk The Wahine, devastated the plantings, which authorities then declared a fire risk and required a $20,000 clean-up operation. Unable to afford the cost, he sold the land and developers bulldozed the site clear.

In honour of Linden’s grandfather, the couple decided the regenerating bush on the five hectares of steep land above the river should be legally protected in perpetuity. It would safeguard the habitat corridor and ensure ongoing erosion control. They approached the Queen Elizabeth II National Trust (QEII) to place a covenant on the forest.

“It couldn’t have been easier,” says Richard. “The local representative visited and we walked around and chatted about our hopes and dreams. They were friendly and knowledgeable, and encouraged us to bring up any questions. Because of Linden’s grandfather’s experience, we like the fact it can never be repealed. And it cost nothing. They paid for the survey and legal costs.” He says that they even get a $45 rebate on their rates. When I ask the couple about how this might affect their retirement plans, Richard points out that it is uneconomic land anyway – too steep to be grazed or cropped.

They negotiated the terms of the covenant with QEII, stipulating that they wanted to be able to establish tracks and install seats throughout the covenanted area and continue to eco-source seeds from the bush. In return they would provide ongoing pest and weed control.

Bringing back the birds

Linden’s morning walk involves checking the five DOC200 traps Thames Coast Kiwi Care have provided for mustelids (stoats, ferrets and rats) and three Timms traps for possums. They have tried poisons and other traps over the years and now feel these are the most effective and humane. Occasionally they’ll set a live cat trap or call a local hunter to deal with a feral pig. Goats are controlled by the Department of Conservation in the neighbouring park.

Magpies were terrorising the native kākā so Richard obtained a gun licence and a .22 rifle but the cunning birds see him coming. His tally averages about one magpie per box of bullets.

Judging by the number of native birds returning to the area, the Moyles’ pest eradication efforts are proving very effective. In 2006, a survey of kiwi calls estimated 14 pairs of adult Coromandel brown kiwi lived in the 1000 hectares of the Te Mata valley and the neighbouring Tapu valley. A 2021 follow-up survey indicated over 48 pairs now reside in the same area – an outstanding success that defies the 2% decline rate nationally.

Linden smiles as she recounts telling a visiting wwoofer that no-one sees kiwis running wild in New Zealand, only to have one run over his foot a couple of days later. Now they hear kiwi outside their bedroom window and have noted at least 25 other species of birds, inhabiting their bush.

Their biggest task was removing the wilding pines. Some were huge with 62 growth rings. QEII provided a chemical ringbarker, which Richard painted on the trunks, but they weren’t happy using such a strong herbicide. A forester progressively cut out at least 100 more, and a storm in 2007 felled eight large trees – pulling up huge root balls which, to the Moyle’s dismay, caused subsequent erosion. They eventually hired contractors to fell a further 16 large trees – an exercise which Linden ruefully claimed cost more than her daughter’s wedding – and are now left with just two gigantic rogue pines towering above the regenerating bush. These are so large that a windfall branch that dropped in 2021 will provide the couple with enough firewood for the next five years.

Battling the weeds

She knew it when it was just a seed, now the kauri towers over Linden.

Weed control in their protected forest is an ongoing battle. Each summer they systematically work through the block with wwoofers, cutting regrowth pines, blackberry, Himalayan honeysuckle, moth plant, gorse, woolly nightshade and pampas, and then daubing the stumps with glyphosate. Weeds are reducing as the canopy thickens and seed sources are eliminated, and the Moyles’ can now use a drone to locate any interlopers on the steep faces. However, it is still hard work, taking two to three weeks to work through the entire block.

The couple divide the bush into two zones: one they have left to regenerate naturally; and the other that they have planted. They noticed that once the pine trees were removed to allow light onto the forest floor, woolly nightshade colonised the carpet of needles, which then naturally died and rotted into a humus that nurtured regeneration of natives.

The path that once led to gold – the Gentle Annie Mine’s pony trail.

Asked what she would do differently if she was starting again, Linden doesn’t hesitate. “I would just collect and scatter seeds over any bare land. Anywhere there is a slip, or a lightwell. Kānuka seed will even come up through kikuyu grass and shade it out then you can start mixed species under that. Sure, you save a couple of years by propagating but it’s a lot of work.”

While Linden tends to the plants, Richard takes care of the infrastructure and lawns. The couple discovered remnants of a pre-existing track winding up the valley which they have resurrected. It was, they learnt, a section of a pony track that once led up to the Gentle Annie Mine – a gold vein in the stream at the head of the valley which was briefly explored in the late 1800s. Richard has added steps and bridges linking it to

a network of tracks and established a main track from the house to the river and swimming hole – much frequented by their grandchildren in summer. He also maintains mown paths and secluded bush-clad glades amongst the bush on the upper slopes.

Alive and happy

After 45 years of marriage and over 20 years of hard work on the property, Linden and Richard know to work harmoniously together while handling their separate roles. The secret, says Linden, is going with the flow; working hard and accepting what you can do in a day.

“It’s a different focus,” she says. “It’s a mistake to take on a lifestyle block for the end product. It’s a process. It’s about enjoying each day for what you are doing. I never come back from the bush without a smile on my face.” “It makes for a happy marriage,” adds Richard.

When they bought the property, Linden said she would die happy if she established a waist-high canopy of native plants.

Now the forest that she planted towers over her; its unhindered growth destined to sprawl and flourish for many years to come.

“I am happy and not dead,” Linden says as she gazes up at the treetops.

Te Mata River.

WHAT IS THE QEII?

The Queen Elizabeth the Second National Trust Act in 1977 created what is colloquially referred to as QEII. It commemorated the Queen’s silver jubilee, fulfilled the National Party’s election promise to establish a body to advise on “open space” and included a Federated Farmers objective to provide a means to protect features on private land.

The legislation established an independent trust operated by a board of directors with powers to encourage and promote “the provision, protection, and enhancement of open space”.

And “open space” had the broad definition of any area of land or water considered to have value. Eight of the ten statutory functions charged the trust to act as an advisory body, assessing and coordinating interested parties on all matters relating to open spaces. The second to last paragraph, as per the Federated Farmers’ vision, gave the power to execute covenants and acquire land. The final paragraph bestowed the ability to distribute grants.

Over time, the advisory and advocacy role of the trust diminished. Governments changed, the trust felt frustrated that it had no real power, and so the Department of Conservation was formed. Though QEII continues to work with other organisations and submit on policy for local and central government, its main objective today is the covenanting of private land for the protection of biodiversity.

Covenanting provides legal protection for features on private land that endures beyond the tenure of the current owner. It was a concept initially initiated by a farmer, Gordon Stephenson, whose own farm had a stand of bush he thought worth protecting. Other farmers had areas they too wanted to protect for posterity. It was crucial, they decided, that it was to be a voluntary, landowner-initiated process run by farmers, for farmers – an ethos that continues to this day.

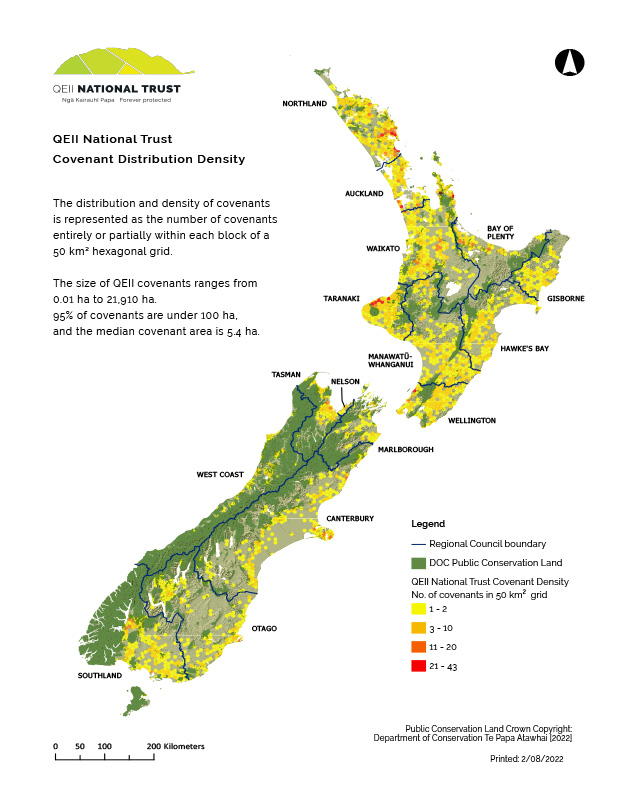

Its success is proven by its uptake. Since it was formed, the QEII has registered 4912 covenants protecting 192,574.7 hectares of private land.

But with 33.4% of New Zealand’s land mass already publicly protected for conservation purposes, the question has to be asked why such protection is necessary. The answer is defined in QEII’s national priorities by which new covenants are assessed. Existing conservation land tends to be high country or uneconomic land. Low country productive and valuable land contains different habitats and different plant species. Priorities for covenants are given to those with threatened indigenous species, wetland and sand dune habitats or other rare biosystems.

The average size of a covenant is 36.8 hectares but it varies from 21,909.62 hectares (Coronet Peak Station) to 115m² of regenerating māhoe-ngaio forest in Island Bay, Wellington. While there is no minimum size, small areas are rarely considered sustainable natural habitats unless they are adjoining another covenanted area.

HOW DOES THE QEII WORK?

QEII has 26 regional representatives throughout the country. These are often landowners with covenants themselves who aim to respect the commitment of other landowners and approach each situation individually. They are the initial contact and provide ongoing support for landowners, evaluating the values, size, connection with other protected areas and

overall sustainability of a potential covenant site.

QEII has the power to protect areas of scientific, cultural or landscape value and exotic plantings, subject to policy and funding.

New covenants focus almost exclusively on rare and threatened indigenous biodiversity.

The covenant is basically a lease agreement and is individually tailored for each situation taking into account the landowner’s requirements and practical management. Landowners will often erect fencing for stock and undertake ongoing pest control, which QEII supports with information and funding. Occasionally, landowners stipulate conditions (harvesting for Rongoā, accessways, etc.) which can be included as long as they do not have a detrimental effect on the integrity of the protected area. The goal is a practical agreement which protects the ecosystem.

QEII then arranges and pays for the area to be surveyed and the covenant registered against the land title. The landowner continues to own the land and the public does not have any right of access. Some councils recognise the covenant with a rate rebate.

The entire process usually takes about two years and once done is irrevocable. If the land changes ownership the covenant stays in place and the landowners’ obligations are transferred to the new owner. In its 45 years of operation, QEII covenants have been legally challenged three times, all by secondary owners. Two have been resolved in favour of QEII but the third, a quarry in the Kaimai Ranges seeking to expand its operations, is now subject to a judicial review claim after being through both the High Court and Court of Appeal.

QEII representatives monitor a covenant and provide ongoing support. Of the 1800 covenants monitored last year, 10% had issues QEII needed to attend to. In these cases, they work with the landowner to protect the habitat and fulfil the covenant agreement. However the majority of landowners value and actively enhance their protected habitat. Studies show that for every $1 the trust spends, private landowners spend $14 maintaining and improving their covenanted area. Kudos must be awarded to the QEII covenanters who not only sacrifice land use, but time and money for our endemic flora and fauna – and our future.

(see https://qeiinationaltrust.org.nz/find-your-rep/)

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.