From Versailles to the mud-brick house

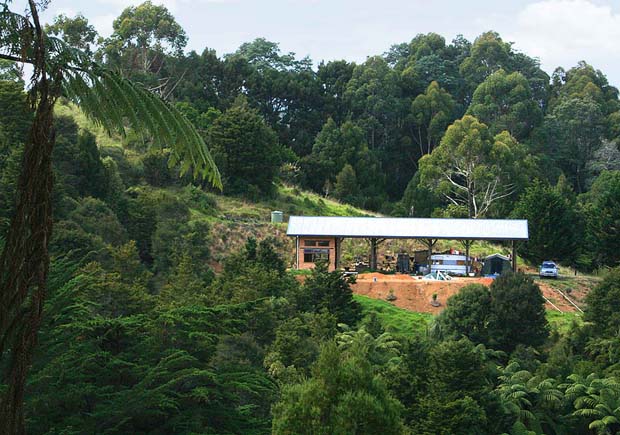

Polly and James’ mud-brick house in the bush begins to take shape with assistance from a Frenchman who helped restore the Palace of Versailles.

Issue 49: May/June 2013

When people warned us that it takes a village to build a mud-brick house, James responded with one of his determined chin juts. “I’ve got a lot of energy,” he told me, which was good to hear because I certainly hadn’t. Ever since baby Vita’s arrival, I’d been consumed by fantasies of Sleeping Beauty’s century-long slumber.

We hadn’t always planned to build with mud. Back in suburbia, when the notion of an off-grid existence had seemed like a beatific state, phrases such as “relatively cheap”, “eco-friendly” and “quick to construct” had seduced James and I into thinking that a straw-bale home was the way to go. Arriving in the Far North, however, we’d discovered an unforeseen problem. This region doesn’t do straw. What it does offer is mud: in spades, if you’re willing to do the shovelling.

And James was. There was a seam of rich, red, volcanic clay slumping by the roadside that we discovered would be perfect for our walls. Upon learning the Council wouldn’t touch this slow-motion slip until it had completely blocked the road, James became civically minded and saved them the hassle, spending eight days transferring trailer-loads of soil to our land. The recipe for mud-bricks came from a local man who gave us a tour of his adobe home. The look of his sculpted house in soft-buttered tones further convinced us that this was our building medium. “It’s bloody hard work,” he cautioned. “You’d be mad to go it alone.”

Eyeing the mountain of dirt now awaiting mud-brick construction, James could see truth in his words. Unable to summon up the labour force of an obliging village, we did the next best thing and signed up with WWOOF New Zealand (Willing Workers on Organic Farms) instead. Despite the caveat that we lack hot running water, operate out of an outdoor kitchen, have a decidedly rustic toilet and live between a tent and a caravan, surprisingly we were inundated with requests from travellers willing to work voluntarily in exchange for their board.

While I picked my way through the candidates, James exhausted our local dump of its newspaper and set to making paper pulp. A truckload of sand was delivered, the soil was sieved and an engineer welded bottomless cake tins for us in preparation for the mud-brick production.

Our inaugural WWOOFers helped lay the first room’s foundations before moving on and then Maxime arrived. A French guild carpenter whose work included restoring part of the Palace of Versailles, he had embarked on a worldwide building mission, hoping to leave a trail of useful constructions in his wake. “I’ll just stay a week or two,” he informed us at the Kaitaia bus-stop when we picked him up, but then he acquired a taste for possum hunting, for cooking over an open fire, for drinking water flowing out of the forest, for the spectacular night stars, the river swims and everything else he couldn’t do back in his city. Better yet, he acquired a taste for our vision and threw himself into the building project, working tirelessly from dawn till dusk for more than five months. Although he wasn’t quite a village, he certainly stopped James from breaking his back.

All through the winter, while Vita and I kept the home fires burning in our rented accommodation, the pair camped up on our house site, endlessly shovelling ingredients into the concrete-mixer and producing thousands of in-situ mud-bricks. By the time Vita and I shifted back onto the land at the start of summer, thick terracotta walls rose up from the earth on which they stood, looking as if they’d always been there and always would.

In the next post, Polly and James shift into their sculpture and go on a treasure hunt.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.