Poultry expert Sue Clarke explains how to feed your hens the correct amount of calcium and grit to lay good eggs

We all want to feed our birds the very best, but do they need extra calcium? Or grit? Or is it all the same thing? Poultry expert Sue Clarke explains.

Words: Sue Clarke

Just about anyone who keeps poultry, or intends to, knows that hens need ‘grit’ to make shells.

The catch is that there are two types of grit, which two different jobs, and they really need both.

1. SOLUBLE GRIT

There is soluble grit which is the sort that dissolves in the bird’s digestive system. This is predominantly calcium-based and can be in the form of limestone (calcium carbonate), either as small chips or ground flour in commercial poultry feeds, or crushed oyster or mussel shells. You can also make a DIY soluble grit out of and crushed eggshells.

Soluble grit needs to be provided in a separate dish to a hen’s main diet. A commercial poultry feed will already include this type of grit in it, so eating more than that should be free choice to hens who need more. Forcing a bird to eat too much calcium (by mixing it into their feed) can be toxic.

These different forms of ‘grit’ are essential to eggshell formation.

2. INSOLUBLE GRIT

The second form of ‘grit’ is insoluble and stays in the bird’s gizzard*. It is comprised of things like small pea-sized gravel chips or small stones which birds pick up if they are allowed to fossick around outside.

These stones do not dissolve and do not provide calcium. Instead, they tumble around in the gizzard, a hard muscular pouch situated at the top of the intestine, to help grind up the fibres in vegetation and crack open the hard husks of grains and seeds that a bird may eat.

This grinding allows the nutrients to be worked on by digestive enzymes and absorbed into the bloodstream. Birds fed a diet which consists entirely of mash, crumbs or pellets end up with a porridge-like mix in their digestive system once water and saliva are added. They don’t actually need insoluble grit for digestion, but it still can be beneficial to aid gut movement.

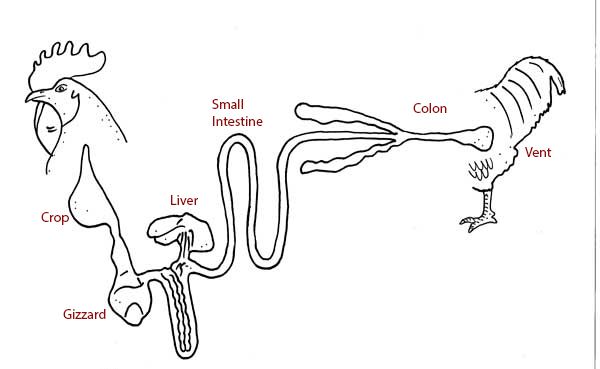

*The crop is the sack at the front of a bird’s chest where it stores feed as soon as it is eaten. The food then travels down into the gizzard for grinding and further digestion at a later time. This is how the chicken keeps itself safe from predators: it can eat quickly, then go somewhere more secure to digest its food. Food then passes through the small intestine and colon, before the remains are expelled out the vent.

HOW MUCH CALCIUM DOES A HEN NEED?

An adult laying hen (over the age of 18 weeks) needs between 4-5g of calcium per day, but she also needs an adequate supply of other elements to make eggshells. These include phosphorous, zinc, magnesium, manganese, vitamin D3.

A commercial layer feed already has all these micro-ingredients included in a vitamin/mineral mix (plus limestone flour at the correct level) to maintain egg shell production.

However, once you start feeding extra grains, kitchen scraps or letting your hens free range, then the amounts of these essential ingredients become diluted if the extra feed sources do not contain the correct amounts of trace elements to make up the shortfall.

The balance of calcium to phosphorous ratio is critical. If you feed extra calcium without extra phosphorous, the ratio becomes unbalanced and shell problems can occur. What most people do when they see a faulty shell is force their birds to eat more calcium by adding it to their mixed feed but this often makes the problem worse.

Never feed extra calcium to birds under the age of 18 weeks, and never feed them layer feed. See ‘Too much calcium’ below for more details.

TOO MUCH CALCIUM

Excess calcium in the diet is excreted as calcium phosphate and this leads to a phosphorous deficiency. Signs of too much calcium or an unbalanced calcium-to-phosphorous ratio are:

- pimply eggs

- eggs with rough ends due to excess calcium deposits

- soft-shelled or shell-less eggs

- reduced feed consumption

- reduced egg production

SUE’S ADVICE

Never add extra calcium either in the form of oyster shell grit or limestone to a bird’s main source of feed, especially a commercially-made layer feed.

If you think your birds may need extra calcium, for example in cases where you restrict the amount of layer feed and make up the diet with other scraps and vegetation, it is better to provide the birds with a special separate dish of oyster shell grit or limestone chips/flour so they can help themselves when required.

WARNING:

Never add dolomite limestone to poultry feed or give it to birds. Dolomite contains 10% magnesium which competes with calcium for absorption sites and leads to a calcium deficiency manifested by poor skeletal growth and eggshell quality problems.

OTHER REASONS FOR FAULTY SHELLS

A funny-looking or missing shell doesn’t necessarily mean there is a lack of calcium in a bird’s diet. A deficiency of Vitamin D3 can also produce faulty egg shells, eggs with no shells and/or birds with lameness problems, ie sitting around, or even deaths. Extra calcium is not going to cure this sort of eggshell problem.

Calcium & layer feed

If a normal layer feed is 4% calcium then a laying hen eating 120g of feed per day gets 4.8g of calcium. During her egg-laying season, she may need up to 5g of calcium or more per day. If you supply extra soluble grit in a separate dish in the form of oyster shell she can help herself when she needs it most, usually in the late afternoon when she is forming the shell for the next day’s egg.

TOO MUCH CALCIUM

A diet containing too much calcium can be a serious problem for young chicks and growing birds under 18 weeks of age. The recommended level for calcium is 1% or below for these birds; layer feed has up to four times this amount, so you should never feed it to birds under 18 weeks.

The excess calcium has to be excreted by the kidneys in the form of uric acid. It is easily converted into crystals which then block the tubules of the kidneys. This can lead to death, often several months later when the stress and metabolic demands of laying eggs starts, or if they contract a disease such as infectious Bronchitis (which also can affect the kidneys).

Too much calcium can tie up phosphorous, making it unavailable. It can also cause rickets (soft/rubbery bones), the same as if they were getting too little calcium.

A diet which includes 2.5% or more calcium fed to young birds can cause visceral gout, nephrosis and calcium urate deposits in the ureters leading from the kidneys, and sometimes high mortality.

Feeding a mixed diet to chicks which includes layer feed plus other scraps mixed in may reduce the serious incidence of kidney damage from the extra calcium, but it may still cause long-term insidious damage. The layer feed would have to be less than a quarter of the chick’s daily intake of food, and then you would have to aware of the calcium levels of other foods you might add like yoghurt, milk, whey or even dog roll, as these can have a reasonably high calcium level.

Chicks and growing birds have a relatively small appetite so even feeding them 50% layer feed and 50% scraps or wheat or greens means they would still be getting twice as much calcium as they need.

If you change from Chick Starter or Grower feed over to layer feed too early (before 18 weeks), young birds will also consume more water than they need, resulting in wet droppings and scouring. This will tend to carry on through the laying cycle as well, a condition many put down to worms. A bird with persistently white faecal-stained feathers below her vent during lay may just be showing signs of being fed layer feed too early in life.

TOO LITTLE CALCIUM

A shortage of calcium in a layer hen’s diet can also cause serious problems. Along with poorly-shelled eggs, she may exhibit osteoporosis and be unwilling to stand due to weak leg bones.

On a slightly less obvious level, a calcium shortage in high-producing modern hybrids like Brown Shavers and Hylines will cause poor egg production.

In order to lay an egg per day, a hybrid draws upon the calcium in her bones to make up the shortfall. But after a couple of days of bone calcium depletion, she will take a day off egg production to replenish the stores. In a modern hybrid – capable of laying an egg per day for 30 or 40 days without a break – this will show as fewer eggs than she is capable of.

In a heritage breed which you do not expect to lay as many eggs, this lack of production may not be noticed. This is brought about by not feeding enough layer feed to birds on a daily basis, or not having extra oyster shell freely available, or bulking out what is fed using high fibre, low-nutrient feeds like vegetables or wheat.

This feeding regime is usually done in an effort to save money, but you need to work out if it makes economic sense to produce less eggs on cheap feed.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.