Why Ōtāhuhu artist Lissy Cole is hooked on colourful crochet (and owns the word fat)

Lissy Cole’s pink cape is made from a repurposed Rumala Sahib, which are used in Sikh religious ceremonies and burnt traditionally. But Auckland Sikh temples donate them to the community.

An artist has found joy after great heartbreak by connecting past and present with loops of hot-pink yarn.

Words: Emma Rawson Photos: Jane Ussher Additional photos: Sheryl Burson

Lissy Cole understands “first up, best dressed”. The youngest of eight daughters learned early on how to get the pick of the clothing pile.

Her evenings were a similar battleground, her older sisters calling dibs on the only telephone, its cord stretched to the limit from the hallway to the privacy of the front room. It was engaged for hours.

And poor Dad, the late fashion designer Colin Cole, was ever-frustrated trying to arrange a ride from his Parnell workplace to the family’s Epsom home.

Her Frida Kahlo and Tekoteko artworks were carved from polystyrene by Lissy’s husband Rudi and then covered by Lissy in crochet for a PARK(ing) Day installation outside Māngere Ōtāhuhu Arts Centre in September 2018. PARK(ing) Day is an annual global event where artists transform public open spaces to highlight the importance they play in improving the quality of life.

Sunday mornings were a different story. Then, little Lissy went to her father’s studio to watch him working overtime designing gowns for the likes of Dame Kiri Te Kanawa. He was often “so blimmin’ busy”, he didn’t see Lissy sitting in the corner cutting ragged chunks out of eye-wateringly expensive imported silk and chiffon.

“I just loved touching the fabrics — beaded trims from France, delicate lace from Switzerland.” On Monday morning, the seamstresses cursed the holes in the silks and the missing bobbins and broken needles on their Singer machines. But Lissy’s teddies were always the best-dressed in town.

A photo of Lissy’s father, the late fashion designer Colin Cole, hangs in Lissy’s sewing room. Colin was one of the country’s leading designers from the 1950s until his death in 1987, best-known for his elaborate gowns and debutante dresses. Read more about Colin at nzfashionmuseum.org.nz

These days, Lissy has moved on from her penchant for Swiss lace. Her current affliction is neon yarn. But there’s a problem. The yarn brand, Love Crafts, has discontinued her favourite shade of fluoro-pink. She used it to crochet a cover for a one-metre high tekoteko (carving of an ancestor).

She also used it for the crochet overlay she made for her 1991 Mitsi Mirage. The car, called The Joy Ride, attracts high-fives, honks and selfies wherever it goes. Its multi-coloured outerwear took three weeks to make.

Lissy’s home in Ōtāhuhu, Auckland, is a rental so she can’t paint the walls. Instead, she covers them with colourful bunting and art.

“When people ask me why, I say, ‘Did it make you smile?’ ‘Yes?’ Then job’s done. Dad would get it.” Colin died of heart failure when Lissy was 15, and while her crochet work is streets apart from his couture gowns, she knows he would love it.

“I crochet because this world is crazy, and crochet brings me joy. It is a thread that connects me to my past, my present and my future. I feel my dad intensely whenever I create anything.”

Flower garlands were created for Lissy and Rudi’s wedding.

Lissy picked up the crochet hook for the first time four years ago, and it has barely left her hand since. Her hook is huge, a number 20, and it loops in a hypnotizing flurry of wrists, fingers and wool. Often when she sits in her Ōtāhuhu home crocheting, she zones out in a trance.

“It’s a great activity for clearing an anxious mind.”

Lissy taught herself to crochet four years ago by watching YouTube. “I’ve always done things with my hands. I love working with textiles”.

Before crochet, she had a job in communications. She was so unhappy she often wrote emails handing in her notice, which she never intended to send. Whenever an email announced a resignation, she fantasized about it being her own.

One day, with encouragement from her daughter Jazmin and husband Rudi, she plucked up the courage, pressed “send”, and began life as a full-time artist.

Her crochet hook is a size 20, which creates big loops, and her crochet style is quite free-form, often because she forgets to count her rows. She’s inspired by the loose colourful style of American crochet artist London Kaye.

“None of us is getting out of this world alive,” says Lissy. “I had to be brave. I couldn’t live with that quiet desperation of doing a job I didn’t love.

“I have always felt depression is quite close. It feels like there are sirens in the water that want to pull me to my death. I’ve felt huge grief in my life — my dad’s death when I was 15, my mum’s death a few years after him and, in 2004, my sister Annabel was killed in a car accident.

“Those sirens have been so alluring at times, but I’ve been able to turn my back on them.”

- The zebra in Lissy’s workroom was bought from Craftworkz in Milford before Lissy started crocheting. “I just had to have him”.

- The Mind That Māori crochet hi-vis jacket is a statement about the visibility of Māori. “The symbolism of crochet for me is the connection I have to my tūpuna. It highlights the thread that binds me to whānau, land, culture”

- The Frida Kahlo shrine is one of many pieces dedicated to the Mexican artist. “I admire Frida because she was unapologetically herself”.

- Lissy’s dresser is hand-painted with Frida Kahlo portraits, Mexican sugar skulls and positive affirmations.

- Lissy, Rudi and artist Leilani Kake collaborated on the tino rangatiratanga flag.

After quitting her job, she had a few “what-on-Earth-am-I-doing?” moments. But a chance encounter with former fashion designer Annie Bonza in an empty movie theatre felt like a sign she was on the right path. Annie, a contemporary of Colin’s, encouraged Lissy to persevere and is now a mentor and friend.

Making a living as an artist is another story. Creative New Zealand funded several public crochet installations, called yarn-bombs, including #CrochetYouStay.

The skull piece was created for Halloween in 2018.

This involved Lissy working alongside Ōtāhuhu’s first contemporary art gallery, Vunilagi Vou, and three more South Auckland artists to create three public yarn installations for the Suffrage 125 Community Fund. The state-backed fund recognized women who have led the way in women’s rights. Recipients were announced earlier this year.

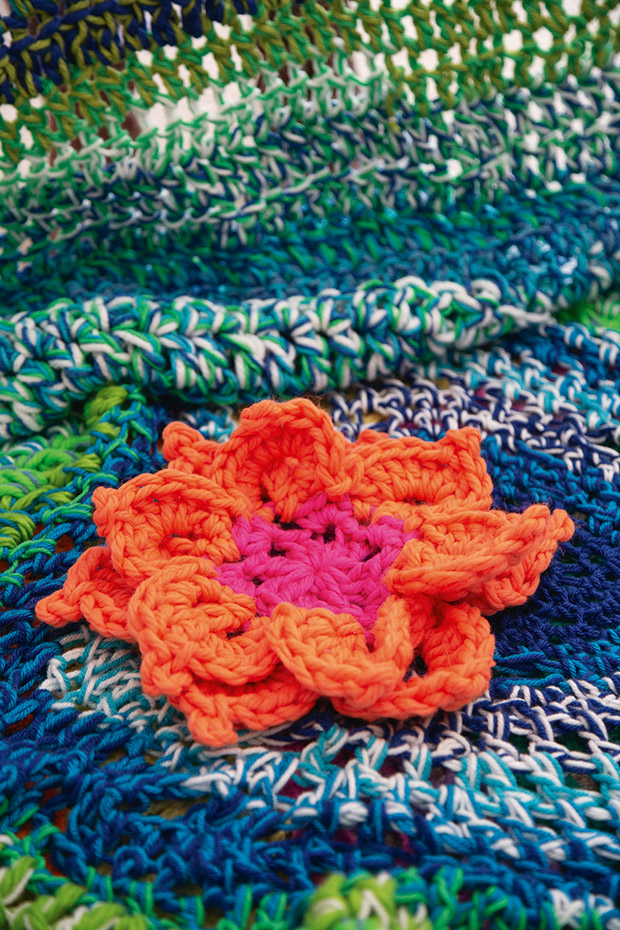

A crocheted lotus flower.

Artistic dreams do not always mean easy financial success and Lissy is grateful to her husband Rudi Robinson, a welding tutor at New Zealand Weld and Trades Services and the Solomon Group, for encouraging her.

Money was tight when she was growing up. While her dad was dressing New Zealand’s who’s who in finery, at home the wolves were at the door. Colin was in fashion for the creativity, not for the money. Lissy’s parents were generous and often took in waifs and strays. The Cole home was always bursting at the seams.

“When you follow your dreams, I genuinely believe the money comes,” says Lissy.

The vibrant shawl was inspired by Dutch crocheter Ellen Deckers.

“Sometimes we might get down to our last few dollars, but something always comes along. Many other artists say they feel the same way. I can’t think about money too much, Otherwise, I’d be in the fetal position with worry.”

Lissy calls Rudi her “Māori McGyver”, and “Goose” to her “Top Gun”. He, too, has learned to crochet and goes along to her crochet lessons at the Ōtāhuhu Library.

“I love teaching crochet, and when people are doing something with their hands, they often talk freely. In one session, a lady opened up about the suicide of her husband. The act itself is about connecting loops, and it’s powerful.

Even the hubcaps and mirrors on Lissy’s Mirage, called The Joy Ride, are covered in crochet. The cover is velcroed on and has to be removed to pass a warrant.

“It’s so good to have a man doing crochet. It’s not just an old lady’s hobby. There’s a big strong fella with a hook in his hands, and his presence makes it feel safe for other men to participate.”

The couple met through a friend. She knew he was the one when he gave her flour (as opposed to flowers). “I had skited that I made the best fried bread, so he sent me flours. Self-raising and high-grade flour, so I knew he was a keeper,” says Lissy.

The Caravan of Dreaming, a 1960s caravan, is too heavy for The Joy Ride, but it goes with Rudi and Lissy on summer holidays, towed by another vehicle, to Sullivans Bay on the Mahurangi Peninsula.

Crochet has been a way of connecting to her mum’s Ngāti Hine and Ngāti Kahu heritage, from which she had always felt slightly distant. Lissy and her sisters all went to Epsom Girls Grammar, and Lissy was friends with the three other Māori students.

“My mum, Mairehau, was Māori, my dad was Pākehā, and when I was at school in the 1970s and 1980s, it was difficult to fit in. I was too white to be brown, too brown to be white.

“My mum was the second Māori woman to win a scholarship to Oxford University, but she never took up the scholarship because she met my father. We only found that out on her deathbed. Her experience of being Māori in this country wasn’t nice, and she experienced a lot of racism, but she came from a generation that didn’t talk much.”

Grandson Christian is a true performer and loves getting dressed up.

Lissy recently completed a six-metre rino rangatiratanga flag with artist Leilani Kake. It debuted at the Nuku Wāhine event held, in July, at Mangere’s Makaurau Marae in the papakainga of Ihumātao. A piece called Mind that Māori, a crochet hi-vis vest, was featured in the inaugural exhibition for the opening of Vunilagi Vou in June.

“Mind that Māori is quite layered. It’s saying be careful with Māori, not because we’re dangerous, but because we are precious as an indigenous people to this country. While it was hanging in Vunilagi Vou, people approached the gallery to ask if the piece was for sale because it looked nice and warm to wear.”

The woollen vest was not Lissy’s first foray into wearable art. When she quit her communications job, she intended to start a colourful fashion label for women sized 18 and up, but she put that aside when her crochet art became popular. She still makes clothing for herself.

“I try to avoid wearing black because that’s what fat people are expected to wear. To stand out as a fat person is an incredibly brave thing,” says Lissy, who’s a size 28. “I’m fat, and I own it, and I own that word. It’s just a descriptor.

“I love my food, and I love cooking it, sharing it and eating it. This is the body I have.”

Lissy’s daughter, Jazmin, is studying towards a bachelor of social work. “She’s nothing like me, she’s very wise,” says Lissy. Granddaughter Mia (nearly two) loves the brightly coloured crochet.

This summer, Lissy wants to throw a “fat babe pool party”. The rules are simple: “If you identify as fat and are a babe, you can come to my pool party,” she says.

Another dream is to crochet a Mini Cooper cover and drive from Cape Reinga to Bluff, installing yarn-bombs and teaching crochet. Lissy’s ultimate goal, though, is to show her grandkids that it’s okay to be colourful, particularly her grandson, Christian, who is already displaying an artistic flair. “I want to teach him that you can live a creative life and express yourself.

“I had a huge generation gap with my mum, and I didn’t know her well. So now I’m an over-sharer with my daughter, and I’ve probably traumatized her.

“I just want my daughter and moko[puna] to know who they are and love who they are, and feel free to be themselves.”

SPINNING A YARN

Yarn-bombing, also known as guerilla knitting or “kniffiti”, is a form of street art where colourful crochet or knitting covers urban spaces. The crochet and knitted installations are designed to add warmth and a human touch to cold industrial areas dominated by steel and concrete.

The art form started in the 1990s when Houston artist Bill Davenport had an exhibition of crochet-covered objects and sculptures. It became street art in the early 2000s when American crochet artist Magda Sayeg began covering bus stops in her hometown of Houston.

Yarn-bombing has since gone global. Large-scale installations include crocheted bridges in Italy and buses in México. Many yarn-bombers have permission from city authorities but, like tagging, unauthorized bombs could

be classed as vandalism, although they are always easily removed.

Solace in the Wind in Wellington. Facebook.com/One-Yarn-Bandits

Yarn-bombing is often described as feminist as it transforms a traditionally female craft into public art. Statues of patriarchs or symbols of patriarchy are targets of cheeky and irreverent installations.

Famous guerilla-knitting examples include a scarf and yellow sunglasses for the statue of Thomas Jefferson at Wichita State University and a knitted pink bikini for the statue of Philadelphia mayor Frank Rizzo. The yellow togs and cap knitted for sculptor Max Patté’s Solace in the Wind in Wellington (above) in August 2011 is one of New Zealand’s most famous examples.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.