A bach-y makeover: A family transforms its West Coast bach into a bright ode to the past

It was serendipitous that the old-style plastic-strip fly screen, sourced from Trade Me, matched the bach’s exterior colours.

A couple of legal high-flyers and their twin girls are now enjoying a slower way of life in a basic-but-beloved bach on the West Coast.

Words: Cari Johnson Photos: Stewart Nimmo

Curious was the weka when he padded towards a paint tray filled with peacock-blue paint. Rumour has it that the feathered intruder stampeded across the tray before retreating to the flaxes nearby. The evidence was not stacked in his favour, according to lawyers Morag Godfrey-Grant and Peter Grant. “The weka had blue feet and a blue beak,” says Peter.

The couple, who live near Hanmer Springs, appreciate that their pint-sized bach in Punakaiki rarely goes unnoticed. On this sliver of land wedged between the sea and Paparoa National Park, it seems that visitors and strangers — perhaps even weka — can’t help but smile as they stumble upon the 80-square-metre dwelling.

Limestone karst cliffs comprise the western border of the Paparoa National Park, which sits some 100 metres away from the bach.

That’s entirely the point. “In the 1940s and 1950s people painted their baches with whatever paint was the cheapest — often a bright, unpopular colour on special,” says Morag. “We wanted it to be properly bach-y and, since painting it, people come to take photos because it’s just so vivid.”

Inside, the three-bedroom bach contains more than what meets the eye. It’s a warehouse of memories and stories preserved over 100-odd years. Laughter rings out in the kitchen during card games at the old rimu table, a stocky piece inherited from the original owners, a couple from Greymouth.

Pāua-shell ornaments and mismatched cutlery tell the story of Peter and Morag, once a couple of ex-pats yearning for New Zealand memorabilia.

The 10-year-old Grant twins, Lexie (left) and Bella (right), don’t usually stand still for long at their family bach in Punakaiki. Souvenirs from their adventures most often come in the form of driftwood, stones and seashells. Their parents are responsible for collecting the more valuable treasures at the bach, such as this fast-rusting metal dragonfly bought at a café in Lincoln.

Their most prized possession, the weathered visitor’s book, is one that had no price tag. It preserves hundreds of reminiscences from visitors over the past century. One visitor in 2019 writes: “We loved piecing together the love story of Peter and Morag through intermittent comments in this very book. The place holds a huge amount of significance for you two.”

Morag first visited the bach with a friend in the 1990s. It wasn’t blue then, but it left her with just as vivid of an impression. “There’s just this wonderful feeling to it. The waves echo off the cliffs and when there’s a storm, the rain pelts down on the tin roof above your head. It’s just beautiful.”

She didn’t bat an eyelid at the building’s less-than-luxurious fixtures. Borer-infested timber? No problem. The rusted remnants of a long-drop toilet? Charming. The young Christchurch lawyer, fresh out of law school, was keen to put her new wages towards something special. “My bank told me I could easily buy a house to which I asked, ‘Could I get a bach?’”

- Peter and Morag won the Edwardian taxidermy seagull in a $10 auction bundle. Says Peter: “We thought, ‘Oh well, we’ll take him to the bach”.

- Peter reckons the artisan who made this shell-decorated box (a briefly popular craft his grandmother tried back in the day) must have run out of shells looking at the strip of Formica laminate around its rim. “She must have used some Formica from one of those old kitchen tables,” he jokes

- Seashell curios, such as this lamp from Trade Me, are always welcome at the bach.

- A souvenir shell dish.

The bach became hers, and she loved it. In the early days, Morag did little to the place except fill it with memories. She recalls drinking whisky with her green-fingered neighbours, bartering for fresh vegetables and whitebait in exchange for gardening space on her deceptively large section.

Friends often came and went, particularly around New Year’s, like the predictable swell of the nearby Tasman Sea.

Life didn’t stay so idle. When Morag met Peter at her law firm, they were married and jetting off to Britain within a few years. They never planned to stay for as long as they did. “The UK was humming when we got there, and we both walked into excellent jobs.

Peter and Morag suspect the rimu kitchen table was built inside the bach in 1924 as it’s too large to fit through any of the doors.

“We were initially going to use the money from six months of work to fund our travel. But, when traveling, both of our employers asked if we could come back,” says Peter.

Slow summers in Punakaiki were replaced with 48-hour getaways to Europe. Their once-bare feet adapted to heels and oxfords; they swapped their jeans for stylish clothes that looked the part on the streets of London.

Morag, an international anti-corruption lawyer, often jetted off to faraway places in the Middle East, Asia and South America. But never once in their decade in London did they forget their small bach in Punakaiki. “The bach has been the one constant that we’ve had in our busy lives,” says Peter.

- Kiwi figurines collected over the years stand united beneath New Zealand’s longest-serving prime minister Richard “King Dick” Seddon, an icon on the West Coast in the late 19th century for his advocacy of miners’ rights.

At the time, it was rented out as a family home, but that didn’t stop the couple from collecting décor for the future. They discovered that eBay and the London auction circuit were brimming with forgotten kiwiana, likely aquired by tourists who visited New Zealand in the 1950s and 1960s. As the old adage goes: one man’s trash is another’s treasure.

The plan was always to return to New Zealand — it just took 13 years, a move to Singapore and the birth of twin daughters Isabella (Bella) and Alexandrina (Lexie) for the couple to follow through. “We wanted to give the girls the type of upbringing that we had. You just can’t get that in the centre of London or Singapore,” says Morag.

The transition to the Antipodean lifestyle wasn’t free of challenges. After the clamour of London, Morag had a tough time adjusting to quiet nights in their historic homestead just outside of Hanmer Springs.

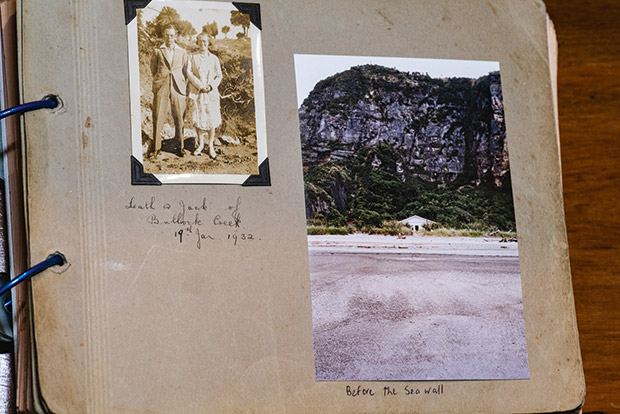

The visitors’ book was presented to the bach in 1932 by Leith and Jack (pictured) of Bullock Creek, a remote valley nearby.

Possibly more painful was the fact that her shoe collection was collecting dust. “We lived in Chelsea in central London, so I’d rarely leave the house unless I were wearing a dress or a skirt and heels. We were used to walking fast, not talking to strangers and dressing a certain way in the big city,” she says.

Punakaiki doesn’t require shoes or a speedy gait — but the bach is surprisingly noisy. This is Morag and Peter’s happy place; listening to the waves rage war against the fortified seawall was comforting to the former city-slickers.

Here, their 10-year-old daughters do what 10-year-old daughters are supposed to: they race barefoot on the beach, sling seaweed at each other and giggle together in their shared bunkroom.

Above the door frame is an image of Michael Joseph Savage, which the couple sourced from Trade Me, a nod to the bach’s West Coast heritage. “Every self-respecting West Coast family in the 1930s would have a picture of Savage,” says Peter. (Savage was New Zealand’s depression-era prime minister.)

“You go to a bach for the simple pleasures — you want to rough it a little bit,” says Peter. Holidayers who book the bach will find it lacking in some modern amenities — say goodbye to that dishwasher and television.

It was only this year that the couple (after much debate) conceded to install wi-fi so Peter could work remotely. Mobile reception is more a luxury than a guarantee, likely due to the limestone karsts cliffs that overlook the bach from the edge of Paparoa National Park.

- Swingball, also known as tether tennis, is best played after the sun settles into the horizon.

- Bella and Lexie are masters at whipping up scones, jam and cream for afternoon tea.

Who needs contact with the outside world? Morag and Peter wouldn’t have it any other way. “I think a bach should be more basic than your house. I was never interested in turning it into a holiday home,” says Morag.

There was only one time they nearly surrendered their bach philosophy. They imagined a two-storey bach so they could see the Tasman Sea, with plans even drawn up by an architect in Greymouth. “Suddenly we thought ‘No! Let’s just let it live as it is,’” says Peter.

That’s not to say the couple didn’t give it a few nips and tucks. After 13 years of little maintenance, the bach looked more tumbledown than terrific. New floors, a coat of paint, a revamped kitchen and bathroom, and some new-ish furnishings did wonders.

- Vintage Kiwiana teaspoons collected over many years.

- It doesn’t get any more local than the family’s Punakaiki Rocks teaware set.

- The twins keep several pāua knick-knacks in their bunkroom, including this Air New Zealand souvenir. “I have a newfound appreciation for pāua. They used to do everything with it — like, why not stick a clock into it?” says Peter.

“Everything is new but old,” says Morag. Adds Peter: “Some of the furniture has been here since it was built; all the crockery is mismatched. We kept that tradition going — the crockery still doesn’t match.”

Life has slowed down considerably since. In early 2020 they returned to Hanmer Springs after another gap year in London. Morag has taken a break from litigation to focus on the girls; Peter now “commutes” to his home office as a consultant to an international private equity group.

And in Punakaiki, the sea is encroaching on an ever-shrinking sliver of land. Peter and Morag remain hopeful their little blue bach will stand the test of time.

“We would like to see the bach remain here for as long as possible so we can pass it onto the girls. It’s nice to keep baches like this around to show the younger generation what baches used to be like,” says Morag.

A SMALL PIECE OF HISTORY

The bach, affectionately named Punakaiki Dreaming, was originally built in 1924 by one of four Ogilvie brothers who ran a sawmill near Greymouth.

At the time, the Punakaiki section seemed to be at the edge of the world; it was the farthest one could travel north on the West Coast Road.

In the 1930s, the bach was passed on to a family of jewelers based in Greymouth. Called the Tennents, they happened to be related to the original owners through Mrs Tennent, a sister of the Ogilvies.

- Peter and Morag sourced the Māori-themed Manor Ware pottery from eBay while they were still in Britain.

- The kitchen showcases an assortment of treasures sourced in New Zealand and overseas, including a tin featuring Queen Elizabeth II. “We are staunch republicans, so we find all the Queen stuff cheesy,” says Peter.

- Cards and board games are housed in Morag’s grandfather’s large kauri tool chest.

The Tennents enjoyed their annual holidays at Punakaiki for another 50 years, making use of mid-century facilities such as the long-drop toilet, a coal range for heating and a generator for electricity.

The bach was sold in 1983 and, in the hands of new owners, was “modernized” with a new indoor toilet, a shower and built-in bunks. Morag purchased the bach in 1995.

She and Peter have retained the ragtag interiors, only replacing furnishings with cast-offs that have a bach-y vibe. Stays can be booked on Airbnb and Bookabach.

WHAT TO DO AT PUNAKAIKI

It took more than 30 million years for pancake-like layers of limestone to form at the edge of Paparoa National Park. The Pancake Rocks and Blowholes are iconic landmarks on the West Coast.

For the most dramatic blowhole action, Peter and Morag recommend visiting at high tide when the sea is heavy. For local swimming, try the crystal-clear waters at the mouth of Punakaiki River (south of the Pancake Rocks).

Choose high tide for deeper waters and low tide for a current that suits boogie-boarding. The Pororari River, on the northern edge of town, is an excellent choice for stand-up paddleboarding or canoeing (hires available in town).

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.