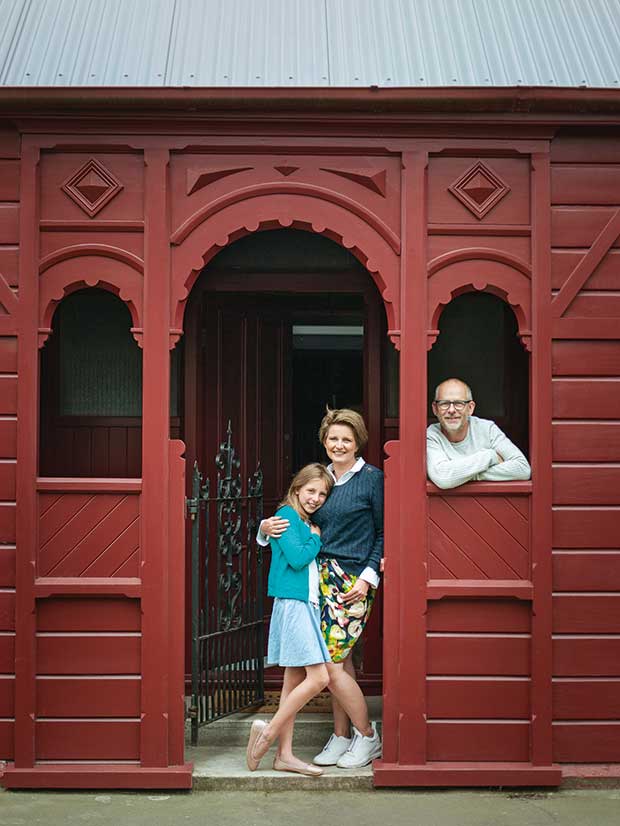

Cranmer Square’s Red House rises again: Christchurch couple Johannes van Kan and Jo Grams pull their dream home out of the ashes

When this Christchurch couple saw their dream home disintegrate before their very eyes, they discovered the Phoenix inside — and skills they never knew they had.

Words: Claire McCall Photos: Rachael McKenna

As giant pincers took great mechanical munches from the parapets of Johannes van Kan and Jo Grams’ once-grand Lyttelton home, the couple watched their future crumble.

The former library building they had bought on the spur of the moment was dismantled from regal to rubble in a matter of hours.

The pair, who met at a photography conference in Brisbane 14 years ago, agree they are impulsive (they met in February and married three months later) but argue it’s a considered spontaneity.

The entrance in the heritage part of Johannes van Kan and Jo Grams’ remodelled home is low and intimate before the space opens up dramatically.

“It’s not a case of being outrageously silly,” says Jo, who emigrated from Australia without hesitation. “When you know what you want, you seize that opportunity and follow your gut instinct.”

But all that was left in their gut on the day the earthquake fatally wounded the “forever” home they shared with their young daughter Ida was a feeling of hollow shock. Where to now?

If you believe in magic, as Jo and Johannes do, serendipity lies around the corner. “Growing up, I wanted to be a magician — an alchemist,” says Johannes.

“I wanted a cook’s kitchen so I started by choosing the oven for its pure grit and size,” says Jo Grams. Daughter Ida (9) likes making (and eating) chocolate soufflé while Jo’s go-to dish is slow-cooked lamb. “Sometimes we’ll do a version of MasterChef where we give Ida a mystery ingredient and we act as her sous chefs.”

Although his school careers advisor sent him along the science path, a naked fire-eater changed that course. Johannes took a photo of the incendiary spectacle, sold it for $10 — and discovered the magic in photography.

Jo, also a photographer, started her career less extravagantly; at 17 she took a job in a Kodak processing lab. From the girl who took passport shots to an accomplished family portraitist, she’s also worked for women’s magazines.

“They called up after the earthquake and asked me to go into the red zone to capture what was happening, but I just couldn’t,” she says. “I thought, ‘I can’t even deal with my own emotions never mind other people’s.’”

The elm tree at the front of the home is pollarded every year or two right back to its knuckles.

It was these qualities — creativity and emotion — that drew the pair to the red house on Christchurch’s Cranmer Square.

Partially obscured by an elm tree that looked like it had ambled out of a Dr Seuss book, the original brick part of the home had all but collapsed. The wooden section, however, designed by architect Samuel Hurst Seager on the southeast corner of the site and added in 1900, was pretty much intact.

- Salvaged ruins are a tribute to fallen buildings — the scrolls were once on the exterior of the couple’s Lyttelton home.

- “One day when we get through more of the essential jobs, we might make them into a wall,” says Johannes.

“The house had piqued my interest when I first moved to Christchurch,” says Johannes. “There was something about the way it was set right on the street with wooden walls, no windows, and just one doorway that gave nothing away.”

Used for years as a bridge club, the property was well known and well loved in the community. Still, no one in their right mind would take it on. It lay empty until spontaneity came a-calling.

Jo’s pet project was the design of the staircase which links the old part of the home with the contemporary addition.

“When we walked in, it just felt like us,” says Jo. “Heritage buildings already have their own magic — a whole bunch of stories, a life of their own and so many things about them that you can discover,” adds Johannes.

There’s that word again — magic. But it takes more than woofle dust and waving wands to transform a protected building into a liveable state. It takes a different kind of circus act: jumping through hoops and over hurdles. It takes stubborn determination. It takes years.

Bookworm Ida settles into a spot at the top of the stairs beneath photographs of Italy and France that Johannes took in the days he was still using film.

In 2012, the couple set about getting resource consent to restore the salvageable part and link it to a new building behind the wooden cottage.

The first plans came in at 50 per cent over budget. They tried again with a different architect. More budget blowouts. They ended up with two resource consents and a building consent, but not enough money to effect the plan.

Dark, painted walls were a brave choice but are countered by the warmth of timber features including the dining table, bought from McKenzie & Willis, which extends to seat 12. Those fortunate enough to receive an invitation to dinner can feast their eyes on two Doc Ross photographs defining despair and hope — a large coloured print of an abandoned earthquake house and a detail image of a feather.

“So we went back to the original idea — a house that said nothing. We always wanted the red house to be the hero of the site,” explains Johannes, “and didn’t want a showy new place to steal that thunder.”

Jo taught herself CAD — computer-aided design — and, together, Jo and Johannes mapped out the interiors to suit their needs before they had a draughtsman draw it up to make it kosher.

Committing to this property has been all-consuming; marrying something old with something new with an ever-wary eye on the something borrowed took a mountain of physical and mental stamina. Johannes, who had picked up a contract to document the restoration of the Arts Centre, would regularly take to the tools once he put down his lens.

The interior of the home studio is painted a neutral mid-grey, a useful background colour for photography that does not affect the image colour.

“We didn’t want to change the heritage part, just bring it back to life,” he says. This included stripping back paintwork. “I think there is a different degree of care when you own the building. It wasn’t uncommon for me to work right through to midnight.”

Jo, meanwhile, was getting her head around a steel staircase that she’d designed as the link between the existing building and the contemporary addition.

“I knew it wouldn’t work with glass or wood, so I approached a steel fabricator and asked them to keep offcuts for the staircase balusters.”

The black-and-white photograph records repairs to the Great Hall at the Arts Centre.

In the end, it took a team four days to put together. “I was trying to emphasize the random — we wanted no symmetry — but it still needed it to be legal.”

Breaking the rules while keeping to the rules is a particular skill but if anyone is up to the task, it’s a couple of magicians.

“It took us a long time and a few battles to understand the guiding principle behind preservation, which is to do as much as necessary but as little as possible,” says Johannes.

“My brief for capturing the restoration of the building was very open and allowed me to take images that were both creative and documentary,” says Johannes; Sometimes we just get lucky and the people we photograph gift us something really special.

They kept the red colour scheme and the beautiful original woodwork around the fireplaces in the cottage but, when it came to the house that, by their own admission, is a simple grey box, they chose the opposite of expected: they painted the interior walls black not white.

They compare the result to the pages of an old-time photo album, where the snapshots sing against the dark backdrop.

Matai floors, milled from fallen trees on the West Coast, bring richness to the palette and tall wooden doors repurposed from their Lyttelton home are the appropriate gateway between what was and what is.

Where once an excavator took their tomorrow apart brick by brick, it has been rebuilt here in a journey of reinvention which, for Jo, has allowed her to identify where her passions lie. They share the restoration with others and operate a bed and breakfast in a self-contained part of the cottage.

It means they have met many like-minded spirits. And Jo enjoyed designing the spaces so much she now runs a kitchen-design business alongside her photography work. “I feel I have worked out where I fit and who I am.”

Jo looks out of the window facing Cranmer Square, an ideal spot for people watching. “The square is the site of the ANZAC parade and has been the location for the thousands of memorial crosses over the past two years. When we first bought the property, there was a festival of whitebait held there which was fantastic but has never returned,” says Johannes.

For his part, Johannes has found real satisfaction in helping to shape somewhere the family want to be. “The build has given me more confidence to be physically creative and taught me about the things that make me happy because I’ve had to fight to get some of those.”

Nine-year-old Ida, who chose the colours for her bedroom — deep blue paint and wallpaper with feathers — often says how much she loves her home. When friends come to play, she’ll sometimes lead them outside to the Dr Seuss tree to show them the ruins that lie beneath it.

- Texture, pattern and colour ensure a family home with vitality.

- The Designers Guild wallpaper in Ida’s room was a design she chose herself.

- Brown mosaic tiles in the bathroom in the B&B are much commented on.

- The freestanding bath in the en suite of the main bedroom was “never going to be white”.

To them, it may just look like an old pile of rocks, but Ida knows the scrolls and square blocks rescued from Lyttelton are part of her history.

“They are simply hints of where we were. We brought them with us to carry on our story,” says Johannes.

MUCH WATER UNDER THE BRIDGE

Although most Christchurch residents know the red house on Cranmer Square as a bridge club, it has a rich architectural heritage.

The first stage, a two-storey colonial cottage, was built — unusually for the time — in brick. Original owner Dugald Macfarlane, evidently a man of means, emigrated from Scotland on the ship Sir George Seymour in 1850.

He bought the section for 150 pounds and built in 1864. Because he ran a wine and spirit business here, it had an underground cellar.

The master bedroom with walls lined in rimu leads to a small deck with a fledgling feijoa hedge. Although the project may look finished (and was featured on the television programme Grand Designs), there is still plenty to do. “Even though I complain about not having spare time, I do still love working on it,” says Johannes.

Between 1871 and 1899, the house belonged to a series of three owners — a farmer/cook, a police sergeant and ultimately a widow who died and left the property to her trustees.

In 1899, well-known architect Samuel Hurst Seager (who designed the Christchurch Municipal Chambers, and Tudor Revival houses such as Daresbury and Elizabeth House) bought the place and made significant changes, notably the addition of a single-storey wooden annex.

The years 1907 to the early 1960s saw an array of well-to-do owners including one Leopold Acland. Leopold is described merely as a “gentleman” on the purchase papers, although his colourful history includes a brush with a tiger that left him without a left arm.

In 1963, the Cranmer Bridge Club raised enough to buy the red house and its members faithfully played here several times a week before earthquakes rendered the building unusable.

Jo and Johannes bought the section in August 2012.

JO AND JOHANNES’ TIPS FOR THE PERFECT PORTRAIT

▷ Don’t let the camera get in the way of a great moment. Know how the camera works and have it ready before you start photographing.

▷ Avoid photographs of people staring at cameras by relating to your subject as a person and through distraction.

▷ Photograph children by getting down to their height; it gives them more presence in an image.

▷ Look for kind light.

▷ Remind people that they need to breathe. When a subject holds their breath, they don’t look relaxed.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.