Four generations’ memories at Rangitikei’s Tyrone farm

Generations of Stewarts have become accustomed to this view – on a clear day it extends from the Tasman Sea to Mt Ruapehu.

For more than 100 years, a Rangitikei farm has been home to one family. Now the fourth generation is putting its own twist on tradition.

Words: Cheree Phillips Photos: Tessa Chrisp

This article first appeared in the May/June 2014 issue of NZ Life & Leisure.

FOUR GENERATIONS OF STEWARTS OF TYRONE

1901-1938 Hugh and Caroline

1938-1964 Harry and Betty

1964-2003 Hugh and Diana

2003-present Andrew and Kylie

A memory lingers in every item in the bunk-house. Children’s books tell tall tales of adventure in their tattered pages, those same pages turned by fathers and sons. The wheels of a tricycle hanging on the wall are rusty, not from years forgotten in the old homestead but from puddles splashed through more than half a century earlier.

Andrew, Kylie and Hannah are used to sharing their home with a variety of pets. When not distracted by a stick, Barney the black Labrador is often to be heard snoring in a sunny spot. Dude the pony makes the most of this by sneaking into the shed to steal Barney’s biscuits.

A globe is mapped with fingerprints, tracing adventures planned and journeys followed across the countries. These are not broken or outdated items to be thrown out or pushed aside but fragments of a living legacy. Each is part of a puzzle, one of hundreds of scattered, worn, recycled pieces that fit together to make a family tree that’s continuing to spread its roots.

Four generations have grown up on this 631-hectare Rangitikei farm. This land has been their playground, their classroom and their home. They have climbed its hills, planted its trees and expanded its flocks, passing on their knowledge and experience to those who follow to shape in their own way.

Families cannot thrive on their own; with partners and wives come fresh perspectives and helping hands. The farm wouldn’t function without their contributions: meals prepared for ravenous volunteers, eyes kept on toddlers, power cuts investigated and ponies wrangled out of vegetable gardens.

Years of growth have obstructed the view but the lie of the land is relatively unchanged by the past century of development.

The matrimonial teams have kept Tyrone, the Stewart family farm, running since 1901 and it’s the latest duo, Andrew and Kylie, who are evolving the business from farm to Rangitikei Farmstay, combining their business dreams with a century’s worth of knowledge and memories.

Andrew’s father Hugh took over the farm from his parents in 1964 and since Andrew took over from Hugh and Diana in 2003 he has chosen paths that might have shocked his predecessors. Despite having his sights always set firmly on a farming future, his decision to head to the United Kingdom, Africa and the Middle East came as no surprise to his family.

Hugh and Diana’s wedding photo adds to the memories in the museum that celebrates the family’s history. Hannah is engrossed in a camera that belonged to her grandparents, above her hang huge saws used on the farm in pre-chainsaw days and Andrew’s old rugby balls sit next to his mother’s childhood rollerskates.

Although Hugh had hoped that Andrew would begin to take over the farm at 18, it was a decade before he received the call from South Africa saying Andrew was on his way home. “I knew the farm would always be here and I wanted to make sure that when I came home I was in it for the long term.”

With expanded horizons and a repertoire of new skills (although perhaps not from his short-lived stint as a professional carpet cleaner) often in demand for running a farm stay, Andrew settled back into life on the farm.

Everything in the bunk-house was found on the property. Stencils displayed on the wall were used to brand the farm’s wool packs.

His plans were disrupted again when he met Kylie at a rugby game in Whanganui, their first meeting despite having spent their schooldays living within 10 minutes of each other. A hilltop engagement with a ring hidden in a rabbit burrow followed, then a wedding and departure for the Cayman Islands. It was a tough decision to lease the farm but while travelling they realized the potential of their home and its history.

In Africa they saw how businesses such as safari parks offered both accommodation and local experiences to their guests. Suddenly the layers of tools, toys and books stored in every building on the farm had purpose again, transforming a retired homestead and several outbuildings into a farm museum, bunk-house and accommodation for paying guests.

- A family tree of satchels and schoolbags.

- A group of vintage cameras shows the evolution of technology.

- Magazines from the 1970s and ’80s hang on an old ladder.

- The radio and typewriter hark from earlier times.

Nothing is new or straight or shiny. An old circular saw blade is a clock, a candelabra found under a chicken coop has a new lease on life and there is a (debated) story that a wedding present to Hugh and Diana is now serving in two parts as outdoor tables. Kylie sees it as upcycling.

“When we took over the farm we came in with a new approach and our plans would never have become reality without everything that the previous generations had kept. They held onto everything; three generations of children’s games, farming equipment and household items were stored in the buildings.”

Even though Kylie’s connection is more recent, she has embraced the land as if it’s in her blood, giving up her teaching job to spend time with small daughter Hannah and focus on the growing role of the farm stay. In 2013 she won the Enterprising Rural Women Business Award, recognition that allowed the couple to step back and take in what they had achieved.

“We get such a buzz out of sharing our farm. Some people think that because it’s a family farm the farm stay was just handed to us and say, ‘Oh, you are lucky’. We have worked so hard that luck has nothing to do with it. We have sacrificed a lot and there have been moments when we thought, ‘What are we doing?’”

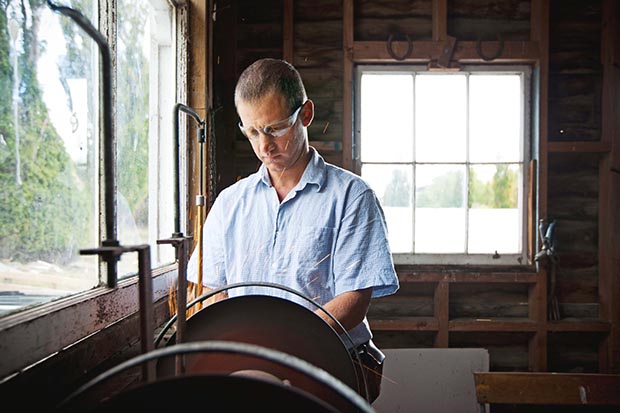

Running the farm with its 2500 Romney ewes and 300 Angus cattle is Andrew’s eight-to-five job while also acting as janitor and fixer for the farm stay and working as a journalist for farming magazines in his (increasingly rare) downtime. A careful eye on budgets meant that all work except plumbing and electrical was done by the couple with help from international volunteers who traded labour for accommodation and food.

Kylie and Andrew are shaping the next generation of Stewart farmers, starting with Hannah in her pink-sheep pyjamas. She took a bit longer than expected to join the family but her parents credit their IVF journey with allowing them extra time to devote to their project.

Colin the sheep was given to the Stewarts by a farm worker named Colin.

At two, Hannah is too young to appreciate the changing face of the farm. Her life is much like it was for her dad and granddad. Days are filled with feeding her pet lambs and the ducks at the pond, riding Dude – he with the hard-to-resist attitude and David Bowie hairdo – and picking carrots to feed to said cheeky pony.

It’s the best playground and, as she begins to see over the fences and past the sprawling paddocks, it won’t be forgotten. She may change direction, heading for distant shores or towns bigger than Marton, but home will always be here.

Kylie’s fruitful vege patch is a continuing temptation for Dude.

One day her pink backpack might hang beside the four generations of old leather satchels lined up in the bunk-house as in a school cloakroom – another Stewart with her own story, just like those before her.

THOUGHTS FROM THE PAST

Hugh: “Growing up on the farm in the 1940s was glorious. We would spend hours down in the creek catching eels and the Maori family living in the cottage would cook them. We were best friends with the kids next door; we would play for hours, throwing mud at each other. There was a school at the end of the road with 30 kids and one teacher but it closed years ago. We used to get a good bounty for possums. If you sent the skin and ears to Internal Affairs you would get two shillings and sixpence. We were sending in 20 or 30 at a time; it was good pocket money. We never see a possum now.

In the 1980s the original homestead was deconstructed, part of it moved to the side to make room for the new home where Andrew and Kylie live.

“When I took over in 1964, the farm was coming from a period of development and growth thanks to the Korean War. Wool was booming as it was used for making soldiers’ uniforms. When I started, there were 1150 ewes. That grew to more than 4000 during our time. We planted a lot of willows and lombardy poplars throughout the farm because when you have a bad drought you can fell them and feed the entire tree to the stock. Their roots spread for about 30 metres so the ground is secure when we have bad rain or drought.

Andrew’s horse Sweetie has been his companion for almost two decades. When he was 21 and Sweetie was four, they worked on one of the last big cattle drives around the East Cape.

“Back in the early days, gorse was used to subdivide paddocks and show boundaries. Unfortunately it took off and we spent years trying to get rid of it. Everything was done with horses. There was no tractor until 1966 when we bought a Ferguson – we still have it.

“When our kids were growing up they would spend hours making huts out of old fencing battens and barbecues with bricks. There were no neighbours for three kilometres so they had to make their own fun.”

The bird house was a pre-wedding distraction project for Andrew.

RANGITIKEI FARMSTAY

– The heart of the farm stay is the old homestead, now a bunk-house and communal area for visitors with a kitchen, lounge, projector with PlayStation games and a TV. It also doubles as a museum, with memorabilia on every wall and explanatory notes. – The bunkhouse is self catering and guests have access to the enormous vegetable garden. “We are big on paddock-to-plate dining, or paddock-to-pony as guests love picking carrots for Dude. When we took this on, I suddenly had to learn how to cook a meal for 40 people. My go-to are gourmet burgers and a slice with Annabel Langbein recipes making frequent appearances.”

– All activities and meals need to be booked in advance by guests. “A lot of activities like walks or feeding the ducks are self-guided or guests can just hang out here and lie by the pool. If there is something going on like mustering or shearing we will show them but normally we just go about our normal lives.”

The candelabra and clock in one of the guest rooms were both found objects.

– “We see a lot of local visitors and international guests and want to show them that real Kiwi experience. This is the only holiday some people get all year so we make sure sure it is memorable for them.” rangitikeifarmstay.co.nz

DOWN TO BUSINESS

Kylie: “This [running the business] has to be your passion and, if it is, just go for it. Believe in your product and you won’t feel as if you’re going to work every day.”

Andrew: “Doing it yourself isn’t always the cheapest or easiest option. It will probably take you four times longer than you expected and if it goes wrong you will need to bring in the experts to fix it up (it’s yet to happen to us but we are always wary!).

“Utilize your existing materials and expertise. We did everything from scratch, using what was available as we wouldn’t have been able to afford it otherwise.

“Finally, be realistic about your expectations.”

Highs: “A high point has to be when Kylie won her award. Sitting down and talking about what we had achieved put everything in perspective and it was great to see her receiving recognition on a national stage.”

Lows: “Maintaining and running the farm and farm stay can get hard when you have everything going on and have to make decisions that affect such a large property. It takes a real effort to maintain the energy and enthusiasm and make the time.”

Challenges: “The farm stay is part of the farm so what affects one affects the other. The drought in 2013 was particularly hard; we had to get water tankers in and close the pool. We are pretty easy-going most of the time but that was stressful. We didn’t know when it would end or what long-term effect it would have on the farm and business. We had to make tough decisions and use the processes that we had in place. There is nothing like the sound of rain on the roof.”

This article first appeared in the May/June 2014 issue of NZ Life & Leisure.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.