Growing coffee plants in New Zealand’s temperate climate and how to roast fresh beans

New Zealand’s first commercial coffee growers share the secrets to growing coffee plants in our temperate climate.

Who: Rob & Carol Schluter with Gino the dog

What: Ikarus Coffee

Land: 2ha (5 acres)

Where: Pekerau, on the ridge between Rangaunu Harbour and Doubtless Bay, 160km north of Whangarei

Web: www.ikaruscoffee.co.nz

There’s a lot of technical detail in growing a good coffee plant. Get the temperature, humidity, soil and water right and the plant will grow and produce cherries with a plump bean inside.

As with wine, there’s terroir which has a significant impact on the flavour of the final brew. Terroir (pronounced tear-wah) is a mix of all the environmental factors that affect the final crop’s taste profile including soil, sunlight levels and climate.

Differences in terroir account for how you get the same variety of grape producing a different-tasting wine depending on whether it is grown in France or NZ, and it’s the same for coffee.

“Our soil, Taumata clay loam, does not need irrigation as it naturally retains moisture,” says Rob.

“The quality of clay as a growing medium enhances sweetness and gives a full-bodied character. If we were on a sandy, peaty soil we’d have to pump up water and you’d have a different flavour profile.

“It’s a huge amount of variables which makes growing so interesting.”

Rob and Carol started with five Coffea arabica plants, but have now grown more than 700 trees.

Being the only commercial coffee plantation in NZ has some benefits. The plants seem to be resistant to viruses associated with humidity and there are no known diseases.

READ MORE: Inside NZ’s first coffee harvest

Worldwide, there are around 900-plus pests – mostly beetles, moths and insects – that like to maim or kill off coffee plants but it would seem none are in Pekerau. About the only problem so far is rabbits getting their daily caffeine fix by ring-barking plants.

However, the couple is vigilant.

“There are lots of potential pests, possums, peacocks, turkeys – basically they devastated our olive crop,” says Rob. “We had enough for ourselves but the birds got most of it. Just behind us, there’s a huge forest which is great for wildlife but not us.

“But we’ve only got five acres so it’s easy to patrol and manage as a small grower.”

The couple’s 700-odd trees are mostly three to five years old, not quite at maturity (years 7-8). This year’s harvest was the biggest so far, with the picking of the ripe cherries starting in early December and continuing through until late January. Rob and Carol picked daily to get the cherries at the point of ripeness. This was done by hand, as quickly as possible at a rate of 7-10kg per hour between them.

A few of their plants reached 4-5m high on their banked property, impractical for hand picking. Part of their learning has been the art of pruning to keep the plants at a useful height, around 1.7-1.8m high. Pruning is experimental, and Rob decided to get a bit brutal with one overly-enthusiastic specimen.

“I stumped it, took it down to knee height – that’s what they do overseas because there’s a lot of root in the ground. You’re doing a lot of selective pruning and it’s quite involved. That’s why I’m looking for varietals that are low maintenance, naturally well-formed and we’ve got a few types that seem to be more compact.

“We’re not going to be quick about saying ‘OK, you lot are coming out’. We’re going to give it more time and analyse it, and selectively replant and develop from the best plants, the best performers.”

Freshly-picked beans first go through a machine that removes the skin and most of the flesh around them. After fermenting in water for 24 hours, they are dried on racks.

Once picking is over, the cherries are put through a pulping machine to remove the skin and most of the sticky flesh around the bean. The skins are dried (see below) and the beans are fermented in water for 24 hours to remove any remaining mucilage which could cause mould growth and ruin the crop. Beans are successfully ‘washed’ when they stop feeling slimy and start to feel rough, like a pebble.

The washed beans are then placed on large drying racks for a couple of weeks. Rob uses a moisture meter to get the drying time right, waiting until it’s around 10 percent. Beans are ready for the next stage when the outside begins to look and feel like parchment paper.

“It’s called parchment coffee for that period of time and it actually improves the flavour by conditioning the coffee (bean),” says Rob. “Then we hull it using another piece of equipment that we brought in from China.

“It’s a 400kg piece of machinery and we’re just figuring out how to work that thing. It nearly reaches my elbows and you’ve got to crank it to start it. We’ve had to do a few adjustments because it was for rice crops. The parchment dissipates and that leaves just the beans.”

Rob says he does wonder if his life could be easier.

“There are phases when I think ‘what the heck is going on here, this is crazy, definitely this is not going to work. Why didn’t I grow citrus like everyone else?’ It would have been a more sensible option.

“But I just don’t have an interest in growing anything else. When you’re involved with coffee you just want to grow coffee.”

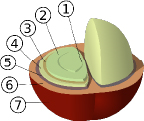

THE STRUCTURE OF A COFFEE ‘CHERRY’ AND BEAN

1. Centre cut

2. Bean (endosperm)

3. Silver skin (testa, epidermis)

4. Parchment (hull, endocarp)

5. Pectin layer

6. Pulp (mesocarp)

7. Outer skin (pericarp, exocarp)

GETTING THE ROAST RIGHT

Rob and Carol have learned from the experts, travelling to the US to learn the art of roasting, the final crucial step. But since it’s their main business to roast and sell imported coffee beans to cafes in the Far North and at farmers’ markets, this is the easy part.

“We roast it when there is demand, so we roast a small batch with a coffee roaster and we try and keep it as fresh as possible for sale, within a few weeks.”

Roasting depends on the sweetness and the size of the bean, says Rob.

“Like when you’re making a cake; if it’s a sweet cake it will burn quicker than a savoury cake so it depends on the sugar content as to how we roast it.”

The flavour of this year’s harvest is still unknown. Rob says there will be more experimenting to see what they get and how to get the best out of it.

“It’s all about flavour and tasting it as well, once it’s roasted. So definitely we’ll be making decisions on how it profiles after the first batch. There’s a lot of variables, whether we put it through an espresso machine, or people put it through their own system at home.”

Customers are curious. They’ve already had interest from people visiting their website and farm, from overseas, and by word of mouth. Rob can’t wait to hand over that first cup.

“I love making coffee, still. After 14 years, I’m still very passionate about every cup that I put out to my customers. There’s something about taking it from a seed right through to the cup and handing it to a customer that is very special.”

HOW TO EAT YOUR COFFEE

The glowing red jewels that fill Rob and Carol’s harvest baskets look like a slightly odd cherry crop. The bean inside is used to make coffee, but the entire plant is edible, from top to bottom.

“It’s really a very nourishing fruit,” says Rob. “The skin you can chew and suck the sweet juice. It’s nourishing and a source of food for indigenous peoples. It’s very high in antioxidants and polyphenols, more than blueberries.”

The skins can be dried into leathery strips (pictured above) and then brewed to create a unique coffee ‘tea’, something Rob and Carol also plan to produce.

Coffee cherry tea is known as cascara (the Spanish word for ‘skin’ or ‘husk). Technically it isn’t a tea – which can only be the dried leaves of the Camellia sinensis plant – but a tisane (pronounced tea-zarn) or ‘herbal’ tea, an infusion of something like dried fruit, berries or herbs in hot water.

It doesn’t taste of coffee either. Rob says their brewed skins taste similar to the sour notes of tamarind. International coffee aficionados describe versions of brewed cascara as sweet, with notes of rosehip. But it seems it’s all down to taste; others mention hibiscus, cherry, red currant, mango and tobacco.

The caffeine content depends on the ratio of water but has been found to be about a quarter or less of that of a cup of brewed coffee.

Source: www.freshcup.com

HOW TO MAKE COFFEE CHERRY TEA

The Square Mile Coffee Blog hot tea:

1-2 heaped tbsp (5-7g) of dried coffee cherry skins per cup of just-off-the-boil water, brew for 8 minutes, then strain and serve.

The Verve Coffee Roasters’ website cold version:

6 tbsp dried coffee cherry skins in 300ml of cold water, leave to stand in a fridge for 24 hours, strain and serve.

However, you can make a coffee leaf ‘tea’ (again, technically a tisane) which Rob is also planning to do. The leaves are dried, slightly toasted, then brewed in hot water to make up an amber-looking drink with an earthy taste, very similar to that of green tea. It doesn’t taste of coffee and only contains small amounts of caffeine (about 10% of brewed coffee) but has all the health benefits.

READ MORE

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.