Whanganui artist Fleur Wickes digs deep to create her emotionally fueled paintings

This Whanganui artist calls her work ‘mark-making with paint’ and regards it as helping her to beat crippling depression.

Words: Lucy Corry Photos: Tracey Grant

When she was a teenager, Fleur Wickes wanted to be a doctor. She studied biology and maths, chemistry and physics, convinced that medicine was where her future lay. But a chance comment from a friend set her on a very different path. She still concentrates on the human condition, but her tools are her camera, her computer, her paintbrushes and – occasionally – an angle grinder rather than a stethoscope or scalpel.

“When I was about 16, my sister’s girlfriend at the time told me, ‘I think you’d be great with a camera.’ I had a real crush on her, so I said, ‘OK, then.’ I started taking photos and realized that I loved it. And I particularly love photographing people.”

So Fleur left Whanganui, where her parents ran the rough-and-ready local pub out at Ūpokongaro (“that was an education,”) and moved to Wellington, where she was the youngest person to get into the professional photography course at Wellington Polytechnic, now Massey University. After winning portfolio of the year, plus a scholarship for a second year, Fleur embarked on a new career as a portrait photographer. It seemed a natural fit for someone with a profound interest in others and a strong desire to find beauty in the unconventional.

“I did portraiture because I wanted to give people the gift of feeling beautiful,” she says. “I have a cleft lip and palate and, when I was younger, I had a really flat nose. Kids were pretty brutal, and I got called ‘ugly’ and ‘bulldog’ all the time. I used to think I was hideous, but one day I decided I didn’t want to feel that way anymore. For a whole year, I looked in the mirror and told myself I was beautiful. It sounds hideously cliched or cheesy, but it worked.

“It’s fascinating when you work with women [as a portrait photographer] you realize the nature of things they carry with them about their appearance. I genuinely like the way I look, and I like my body, but I guess I made that happen. I think most people are beautiful and it’s been an honour to be able to show people their own beauty.”

Fleur spent Level 4 lockdown in Wellington with a friend, living in a kind of suspension. “It was a calm, restful, beautiful time, although it started with me freaking out when four upcoming exhibitions were cancelled. But since then, I’ve had an unprecedented amount of orders for my prints/artwork, so I’m feeling very fortunate.”

Fleur’s portraits became sought-after artworks and she amassed a solid following during 20 years as a photographer, traveling the country. But she got an itch to do something else.

“I was making an excellent living in professional portraiture, but one day I decided to draw the words I was writing. I’d done Bill Manhire’s creative writing course and been published in things like [literary journal] Sport, but this was different.

“For me, words are super-emotional and kind of visual. I’m trying to draw them in a way that gets the emotional layering out. I draw them the way they feel to me.”

Fleur struggled to name this kind of work – she still doesn’t call herself a writer, or a poet – but it immediately resonated with viewers. “When I did the Bill Manhire course he said, ‘The more specific you can be, the more other people will be able to understand it.’ I realized that if I drew something emotional to me, people could feel the emotion and put their spin on it.”

As her artistic horizons broadened, her personal landscape darkened. Fleur’s marriage ended, she struggled to care for her son David on her own, and ugly ghosts from her past reared up to confront her. Life turned as black as an exposed spool of film. “I didn’t have a breakdown, but I was a complete mess for about six months,” she says.

“My marriage had ended, and I just had to deal with it. I was barely functioning, but I had no choice. I was living in this beautiful house in Wellington. I was completely broke, and this tsunami of dealing with the past just swept over me. I hadn’t told anyone I was raped when I was 16, nor had I dealt with things that happened in my childhood. Then one day it all came out, and I couldn’t stop it.”

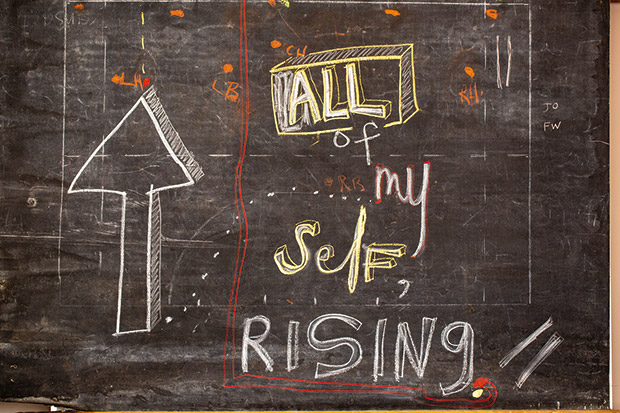

Fleur says Japanese decluttering guru Marie Kondo inspired the work, All of Myself Rising. “She was asked what her definition of joy was and she said, ‘It’s when you feel all of yourself rising.’ I thought that was such a beautiful description of how joy feels.”

Gradually, painfully, Fleur put herself back together – “like a piece of kitsune pottery”, she says. “Before this happened, no matter what I did, nothing I did was ever good enough. But afterwards, I realized that I believed in myself and my work. A lot of the shadows have been released.”

Bravely, she decided she needed to make changes so she could pursue the artist’s life she wanted. She chose Whanganui, for its supportive artistic community and lower cost of living. “I came here so I could work on the art of what I do. I had no money, absolutely nothing.

“There were times when I had to choose between buying tampons, or bananas for my son, but I was determined not to compromise on my art. My work is my way of coming out of the darkness and finding the light.”

A “huge need” to express herself during lockdown led to her drawing every day. The illustrations were then posted on social media with accompanying thoughts. “It became almost a diary of my thoughts and feelings about the time we had outside of our lives, living neither in the world we were used to, or the world that was to come.” The works will be published in an book, called Parentheses, available later this year.

Much of her work is intensely personal – Fleur’s art references the 2016 death of her mother, Colleen, lost love and inner torment. “I’m very emotional, this is my way of dealing with my life,” she says.

“The more I can release all this, the stronger I feel. I love that people put their own spin on my works – what I see in something, other people might not see at all. I put a lot out on social media, and I write a lot about my work, but I’m aware of what I’m saying, and I do keep a lot of my life private. I make plenty of bad artwork – if you’re not making bad art, you’re not making any good work either – but I don’t put it all out there.”

Recognizing that her strengths lay in making emotional connections, she devised a way to showcase her work by holding “art houses”, where she exhibits works in her own home or other people’s. She says these events suit her art more than hanging it in an anonymous gallery space.

The artist admits it’s often hard to part with her intensely personal works. The Greatest Adventure painting was a commission she made for Alice and Caleb Pearson (winners of television’s The Block NZ in 2013) for their 10th wedding anniversary. It hung on her wall for a week or so before she packed it up and sent it to them. “I sometimes find it hard to say goodbye to commissioned works.”

“It’s like a Tupperware party but with me, my art and no Tupperware,” she says. “From a business point of view, I have 100 per cent control. People rarely buy my work unless they have a connection to it. There’s the intellectual or investment angle, and then there’s the gut response. That’s where I make my artwork from, and that’s where people usually connect to it. The art houses are very low-key – I’m not a particularly scary person, and I usually trip over or spill something on myself. People seem to like the experience.”

Fleur’s future looks bright for 2020 and beyond, with commissions lining up for paintings, portraiture and other works. She’s proud to have come this far.

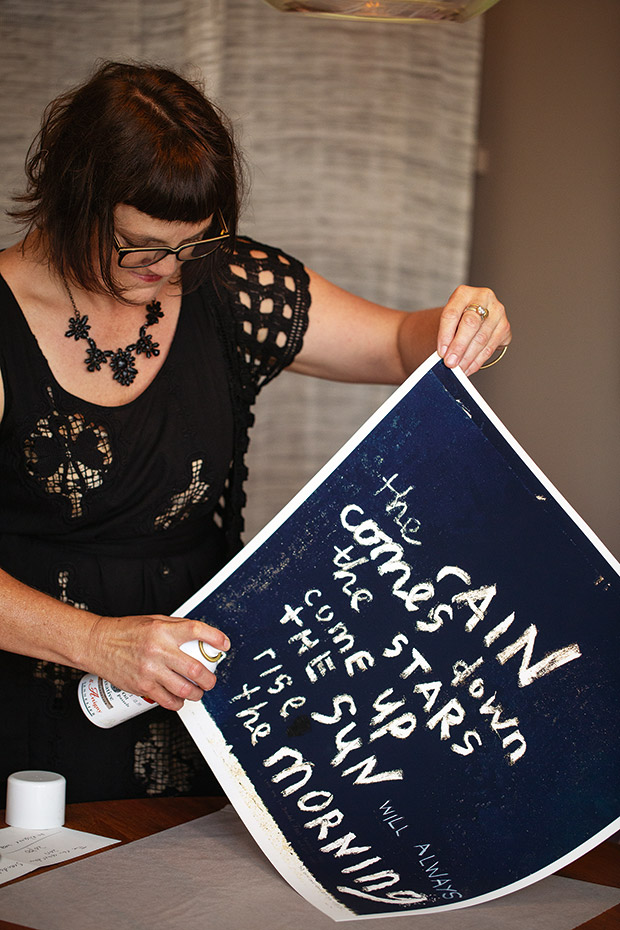

The Rain Comes Down is a limited-edition studio print.

“It’s lovely to be earning a good living and not having to compromise my work. The art of it is the most important thing. I believe that I have something original to say and that I have a long way to go. But the art of it comes first.”

That also means exploring new territory in the form of painting, spurred by a request by a long-term buyer who wanted her to “make a painting on material that looks like it came out of a dumpster”. “I did it on metal, and it took about a year. When I delivered it, she cried because it was so awesome. That was the beginning.”

Fleur describes her painted works – which sell as soon as she can finish them – as “mark-making with paint”. “I can’t ‘draw’, but I am purposefully not trying to learn like I didn’t learn to ‘design’. I trust my aesthetic and my voice, and I’m loving it. It’s a very visceral thing. I know how to take photographs; I’ve been doing it for 30 years. I’m not bored by it, but I know everything technically about the medium. I often purposefully make the photographs look quite rough because that’s the feeling I’m going for. But with working with painting and metal, I’m flying in the dark.”

This kind of darkness is one in which she’s comfortably uncomfortable. “It’s extraordinary when you’ve lived with these shadows all your life not to have them anymore. My favourite book is We’re Going On A Bear Hunt by Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury. The idea behind it is that you can’t go over it, you can’t go under it, you have to go through it. At my worst, life felt completely black. But the key to being able to get through is to find beauty in life.”

IT’S BEAUTIFUL HERE

For the past three years, Fleur has lived in a villa near the Whanganui River with Seth, her staffy-boxer cross. The house, built in 1910, has a small front porch overlooking a garden filled with lavender and rosemary and does double-duty as a home and workspace.

“I had a big studio in Wellington, and then a huge studio in Whanganui. It was the studio of my dreams, but I didn’t get much work done — I was easily distracted. But here I’m more productive. I like the volume of this house — it’s little, but it has what I need. I’m not the world’s best cleaner, so it suits me.

“There’s so much to love about Whanganui. You can park for ages for about a dollar; you can drive across town in five minutes. There are the galleries, of course, and Paiges, a brilliant independent bookstore.

“Experiencing the moods and changes of the river is one of the nicest things about living in Whanganui,” Fleur says. “Walking beside it everyday centres and calms me, and Seth loves it.”

“There are lots of great cafés now, and the climate is wonderful. It’s so affordable, which makes it suitable for young families and artists. I couldn’t work like this in Wellington or Auckland.”

A ROOM OF HER OWN

Painting, sanding and angle grinding are not particularly compatible with the digital tools of Fleur’s photography work, or with finished artwork and exhibition prints. Luckily, she has been able to find a unique space where she can create messier works without disrupting the peace of her home and workspace.

So she turned a tiny 1950s caravan (above) she found “down the road” for $500 into a painting studio. The caravan, named Buz after its 7BUZ number plate, was formerly used to store wood. Now, thanks to several coats of white paint, a good clean and a false ceiling made from white muslin, Buz gives Fleur a proper room of her own in which to work. “It’s very peaceful out there. I love it so much.”

MORE HERE

Ōpōtiki artist Fiona Kerr Gedson transforms feathers into Nepal-inspired mandalas

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.