Woman in the Wilderness author Miriam Lancewood loves a life without walls

Miriam Lancewood lives the epitome of an “open door” policy – except, for the past eight years, she’s had no doors. Or a roof. Or an address. And that makes her very happy.

Words: Lee-Anne Duncan

Few are the same person at 35 than at 27, but fewer still will have changed and grown as much in eight years as Miriam Lancewood.

In 2008 Miriam, who is from the Netherlands, made New Zealand her adopted home, arriving with her husband Peter, whom she met while traveling in India. So far, so ordinary.

It’s around the definition of “home” that things start to get interesting. Miriam and Peter have spent the past nine years living out of backpacks. They’ve been sleeping under canvas, camping in the most remote regions of New Zealand, moving on only when seasons change, or food stock needs replenishing. Then, together they walked thousands of kilometres along the trails of New Zealand and Europe.

Miriam jokes the pair are “homeless” but, really, they’re “home-free”; free of the worries and restraints of owning a home, a car, a phone, a television – anything tying them to a place or taking up space.

“It’s very liberating. If you own something, it takes up room in your head because you have to remember where it is and to look after it. Not having that clears up the mind, with which comes clarity and rest,” says Miriam, from a friend’s house in Marahau, on the golden-sanded fringe of the Abel Tasman National Park.

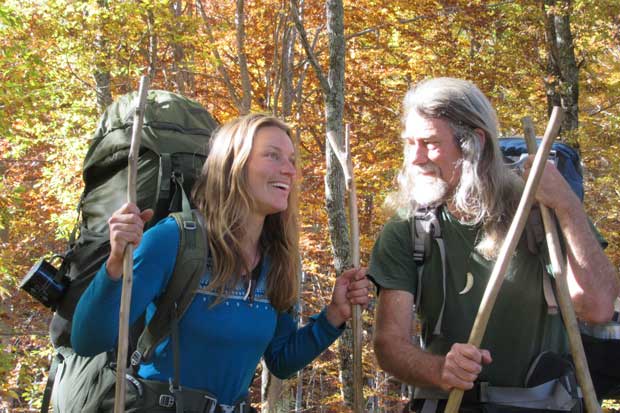

Miriam and her husband Peter walking in Bulgaria.

It’s a short spell within walls while she prepares to appear at the Dunedin and Auckland Writers Festivals in May (and the accompanying media calls).

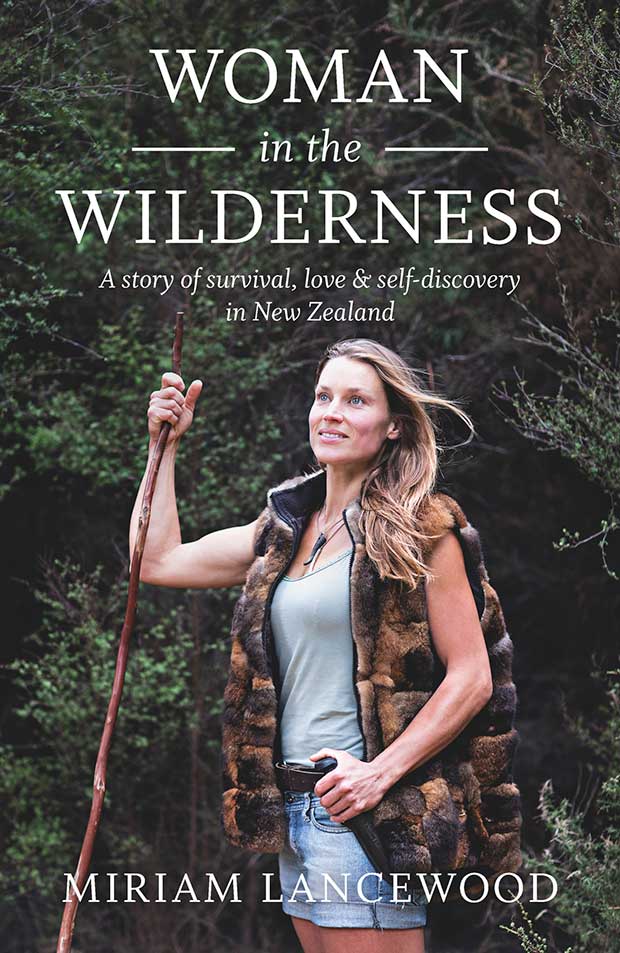

Miriam’s book, Woman in the Wilderness, spans the six years from 2010 that she and Peter camped in extreme isolation around the South Island, and then walked the length of the country over the Te Araroa Trail.

And it’s an extreme tale. It begins in autumn when Miriam and Peter say goodbye to their home and friends in Marlborough and are dropped at a dilapidated hut in the wilds of South Marlborough. With them are two backpacks, 12 plastic buckets of food, and Miriam’s bow and arrow.

“The tent would be our bedroom, the hut our living room during bad weather, the river was our tap, fridge, shower, dishwasher and washing machine, and the whole valley was our garden,” Miriam writes in her book. “Apart from our modern clothes, we could [be] living in the Stone Age. It brought a surprising amount of fulfilment and contentment to be leading such a simple and practical life.”

Sure, many New Zealanders can see the appeal of such an adventure in summer, but this was autumn, and the winter freeze was on its way.

“We’d been reading all those expedition books about people going to the South Pole,” Miriam says over the phone. “What we were going to do in comparison was easy, so we wanted to do something extreme. It gives you your own energy to do something extreme. It gives you joy so you can endure it.”

Peter and Miriam.

It’s not like they were newbies to the outdoors and hardship. Peter had traveled off the beaten track for years, and Miriam retained the fitness of the competitive pole vaulter she had been in her teens. Still, the pair trained and prepared.

“We did a lot of bush-bashing with packs. It’s one thing to walk on a track with a pack, but to walk through thickets and bush on the top of ridges and spurs is something else.

“We also practised walking up icy rivers. We decided to go into the mountains with sandals because with so many rivers to cross we’d be constantly undoing our boots. Sandals are more practical. It was great to train for something that felt like an expedition, and we were very excited about it,” remembers Miriam.

(Miriam always wears sandals, still. “My feet are so broad they’d hardly fit in boots,” she says. And that’s even in the snow, only adding socks when she considers it freezing.)

But she couldn’t train for the challenge of doing nothing. Miriam writes in her book: “For the mind that is focused and runs at high speed, living in nature is extremely boring as there’s hardly anything to do. But, if you take the time to slow down, it’s a world of incredible wonder.”

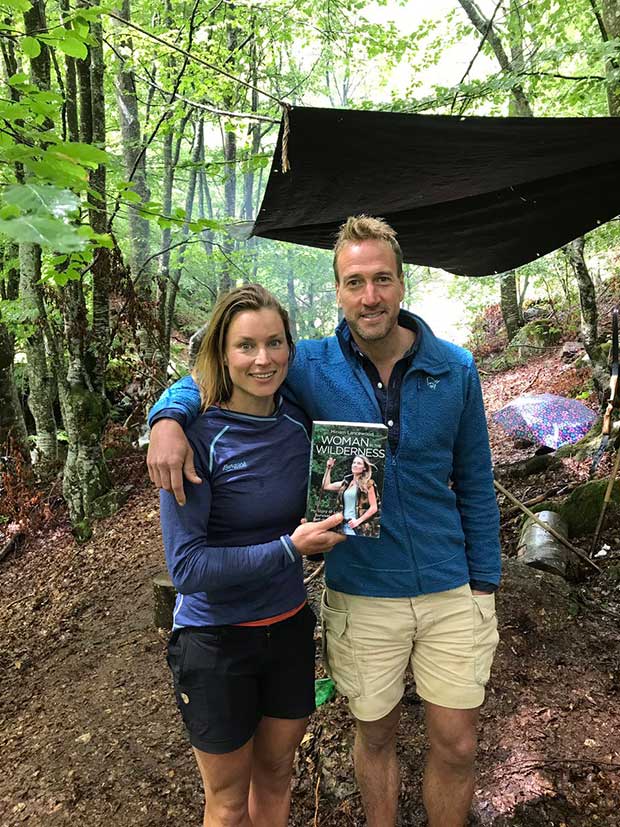

Miriam with Tamar Valkenier.

Nor could she prepare for the loneliness. “Without all the busyness and distractions, I’m confronted with my own fears and limitations, which are not always easy to face… So I’ve started to practice, and every time it becomes a little easier. I sit by myself in the forest for an afternoon, feeling restless and uncomfortable. I have to resist running back to Peter. Then I focus on the beautiful trees and ferns, and I slowly start to feel more at ease.”

Many of these insights are recorded in letters she wrote for her family, then folded into a stamped envelope and entrusted to the few hunters passing by the couple’s campfire.

“Sometimes those letters were 20 pages, like a booklet of stories. That’s been great in the writing process because all those stories come back to me. Very little happens in the bush in terms of visitors, so I can remember our dialogue quite clearly from years back. When we meet people in the bush, it’s such a remarkable event that I remember.”

The book is a fascinating and detailed document of how much this still-young woman learned over those six years. Yes, she’s no longer afraid to be alone – in fact, she relishes her own expeditions into the wilds. She’s learned a lot about relationships, having spent 24/7 for months on end with one man, sometimes trapped in their tent by the rain, playing game after game of chess.

Miriam – until then a life-long vegetarian, and who reverts when out of the bush – has also mastered shooting and trapping meat, mostly goats and possums. The meat gives her and Peter the vital warmth and energy to survive the winter cold.

“Now I feel I can look after myself. Although I’m dependent on my rifle, I can survive by myself in the mountains by myself, and that’s amazing. I’m happy about that. It gives me so much confidence.”

Not only does Miriam well and truly survive in the bush, but she also looks good as she does it. Her skin and hair would be the envy of many models, yet she washes her hair with “the cheapest soap” (or her own urine to banish dandruff) and hasn’t used moisturizer for three years.

“It became an issue when we started long walking, where every gramme is discussed. Peter asked, ‘Will using moisturizer on your skin improve it or deteriorate it?’ I couldn’t answer with certainty, so I decided to try it. I have a few more wrinkles now but probably would have had those anyway from being outside. It’s certainly very practical.”

Since Miriam finished the book, she and Peter have walked 5000 kilometres along various trails through Europe and into Turkey, reveling in Europe’s forests and Turkey’s Greek ruins. “The only disadvantage to walking in Europe is I couldn’t hunt, so we had to buy food in the little shops we came across.”

By the end of that, Miriam says Peter’s days of long walks were done. “Peter said he’d had enough. He hated his pack. I could see that by the way he looked at it. He’s now 65 years old, so his recovery is so much slower than mine. He said he would do more walking but only with a donkey or a robot.”

Miriam’s long walking days were not done, however, and, with her fear of being alone struck down, she put out the word for women who wanted to join her on an expedition in the South Island.

“I hardly ever see women in the bush – tramping, yes, but not off the trails. So, I wanted to attract five experienced hunters to come with me and live off the land, hunting and gathering, for two months. Two hundred women wrote and said they’d love to come, that they were ‘wild at heart’ but most had no experience of hunting, and those that did didn’t have the time. In the end, I went with one other woman, who happened to be Dutch.”

They walked from Arthur’s Pass to Wanaka last January, following no trail, only the topographic lines on a map – and their noses.

“We’d look at the mountain and think, ‘that looks doable’. At times it was scary; we found ourselves on landslides and avalanches, thinking, ‘this could all go very wrong’, as I held my bodyweight and my pack on the one stick I’d planted in the gravel.

“But our main goal was to survive, which we did. And we found meat almost every day.”

Since then, Miriam is well on her way to becoming a television celebrity – hardly a surprise, given her natural telegenic appeal – attracting media attention in New Zealand and overseas, including her native Holland and from well-known wilderness broadcaster, Ben Fogle.

Miriam with Ben Fogle in Bulgaria.

Despite that, she has no desire to be back in “civilization” (generally, media wanting an interview must get themselves to her, deep in the bush, as The Guardian did back in 2017). “In the bush, we sleep 12 hours a day in winter, but when we come to the city, we sleep less because our friends don’t sleep so much. So, in a few days, I feel much more emotional and less happy, more stressed out and worried. Coming back to city life would ruin me.”

With Peter preferring a less peripatetic lifestyle, Miriam says they’re now seeking a small base of their own in the bush somewhere, preferably in the upper South Island.

“We’ll let the thought sit and see what comes up. I’m always curious about what door will open next for us to go through.”

She’s in no hurry. As Miriam writes in her book, “If time is money, we’re millionaires.”

Learn more about Miriam here. Woman in the Wilderness (Allen & Unwin) is available in English, German, Chinese, Dutch and (soon) French.